February 2017 | Point of View

How much customer service is enough?

How much customer service is enough?

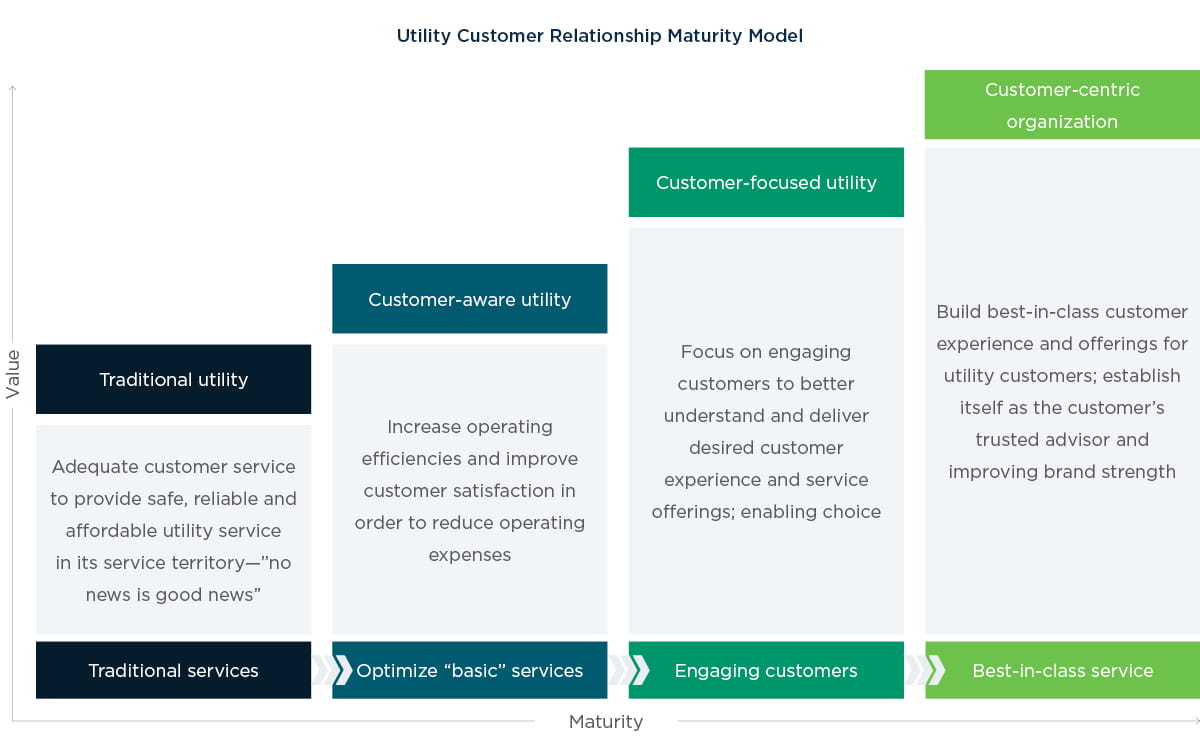

The evolving clean energy economy is driving utilities across the United States to redefine their relationships with customers, as well as their investments in customer service. How much should a utility invest in customer service? The answer starts with the utility’s business strategy. Right-sizing the level of customer service investment requires careful reflection and understanding as to where the utility wishes to position itself in the new energy economy. Additionally, it requires understanding how various investment strategies can improve a utility’s relationship with its customers and position that utility for success in this changing environment. The customer service organization must be aligned to the strategic goals of the utility. Once we determine the future state of the customer service organization aligned with the utility goals, we can create an optimal path forward. The four-stage customer service maturity model provides a framework to determine that desired future state.

This paper reviews factors driving the new energy economy and the diversity among utilities that mandates individualized approaches to customer service based on local regulatory and legislative conditions and customer expectations. It presents a Utility Customer Relationship Maturity Model, developed based on our observations of utilities across the United States. This model includes four key phases of maturity on a continuum that extends from traditional utility operations to customer-centric organizations. This model offers a useful resource for utility executives tasked with making choices that can increase the value and strength of the organization’s customer relationships.

How much should a utility invest in customer service? The answer starts with the utility’s business strategy. ”

Why are customer relationships a key asset in the new energy economy?

Several important factors — e.g., climate change concerns in California, reliability and resiliency in the wake of New York’s Super Storm Sandy, high energy costs in Hawaii, the widespread proliferation and acceptance of distributed energy resources (DERs) — are influencing the way energy is created, delivered, and consumed in the United States today. Industry trends are influencing lawmakers, regulators, utilities, and competitive market forces to converge on the concept of an increasingly decentralized clean energy economy — one with informed energy consumers and significantly more industry participants than yesterday’s model.

This transformation to a new energy future is unavoidable, and utilities are meeting it with both opportunity and distress. Two assets in particular put electric utilities at the heart of this transformation: their traditional indispensable electric grids and their extensive, and sometimes captive, customer base.

For decades, utilities have successfully operated centralized electric grids, albeit with deteriorating infrastructure. Unfortunately, the grid of yesterday is not properly equipped to handle the unprecedented levels of stress that renewable energy and distributed generation bring to this aged infrastructure. Throughout this transformation, utility leaders will struggle to determine which advanced grid solutions will best provide the two-way flow of power and information necessary to successfully integrate large numbers of DERs into the electric grid in order to advance the future of energy.

Similarly, electric utilities will find it necessary to redefine their relationship with customers. Current levels of customer service and engagement are ill-equipped to support industry trends such as rising consumer expectations, legislative and regulatory mandates, and increased competition. Customer experience practices and enabling digital technologies offer a wide variety of opportunities and solutions to help address these industry trends and transform the customer relationship in support of our energy future.

Prior to investing in such solutions, utilities will need to reflect and strategize their own energy future, taking into account many important factors. It is essential to note not all customer service and engagement investments will yield the same benefits from one utility to another. Rather, these benefits are inextricably linked to a complex and dynamic energy economy comprised of utilities, legislators, regulators, competitive markets, and the customers themselves. Right-sizing a utility’s investment in customer service requires careful reflection and examination into these important factors to ensure the utility realizes their benefits and advances its own energy future.

Customer service is not a one-size-fits-all concept

There are more than 3,300 investor-owned, publicly owned, and cooperative electric utilities across the United States. They are governed by a diverse set of regulatory bodies, including public utilities commissions, independent system operators, municipal utility districts, and local governments. These utilities employ a diverse workforce that serves an equally diverse customer base. Some of these utilities experience market competition to varying degrees in areas such as distributed generation, electric retail supply, and competitive transmission. These differences across utilities, regulators, customers, and competitive markets are the key factors that influence and shape the relationship utilities have with their customers and, subsequently, the customer services that each utility provides:

- Channels used to communicate and pay bills: Customer preferences, a utility’s understanding of those preferences, and system capabilities influence the channels a utility offers to communicate and conduct business with its customers.

- Quality of customer service support: Utilities must carefully balance quality customer service support with affordable rates for consumers. This requires focusing on operational excellence and the value of higher customer satisfaction.

- Types of information, products, and services available to customers: Customer usage (AMI) data, new choices in DER alternatives, customer interests beyond the meter, and a wealth of new mobile applications and energy efficiency programs fuel customers’ desire for choice and activate new competitive markets.

- Types of customer engagement: Utilities’ desire for new revenue streams will require more effective customer engagement techniques, beyond traditional one-way communication, in order to drive sustained customer behavior change.

- Degree of personalization and convenience: Increased competition may drive select utilities towards a relentless pursuit for best-in- class customer experience, requiring advanced customer segmentation, mobile platforms that allow fast and complete transactions, effective self-service capabilities, and customer experience market design.

Naturally, there is no one-size-fits-all customer service solution for utilities but rather a continuum of customer solution possibilities that utility leaders may consider given the intricacies of their own organizations and the realities of their external landscape. And while each utility may draw upon a wide range of customer solutions to help achieve its business objectives, establishing a more prudent customer relationship strategy requires understanding how these differences influence the value proposition for various customer service investments.

For instance, there are still a significant number of vertically integrated utilities in the United States. And while 29 states have renewable portfolio standards, the pace and impact of distributed generation varies greatly. For many utilities (including those in Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, Louisiana, Kentucky, Indiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, Missouri, New Mexico, Kansas, and Washington), the impacts of deregulation, competition, and customer expectations are still evolving. In these jurisdictions, utilities (such as Gulf Power, Duke Energy, Southern Company, Vectren, PS New Mexico, CLECO, Entergy, and Puget Energy) are investing in new technologies and focusing on better ways to listen to their customers and improve their service. For these utilities, the J.D. Power ranking can be useful in focusing on key areas of opportunity.

Utilities in states that have taken a more direct path toward full competition and open markets are turning to new technologies, new services, and new organizational structures to respond to regulatory and market pressures. For instance, utilities in 16 states—including much of the Midwest and Northeast, including Illinois, Ohio, Michigan, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and the New England states, as well as Texas, Montana, and Washington—now have to deal with retail choice. In many of these states, customers are no longer captives of their legacy providers: utilities no longer own their own generation and regional organizations manage transmission assets. To win back their customers, many of these utilities are searching for more robust, impactful, and sustainable strategies to leverage their brand and their customer relationships.

For many utilities, the impacts of deregulation, competition, and customer expectations are still evolving. ”

Finally, in just a handful of states, some utilities are undergoing an organizational “re-set,” focused on understanding and delivering customer expectations and services even beyond the meter. Among other things, they are: (a) adding new organizational roles, new structures, and new services; (b) responding to the accelerating addition of distributed energy; and (c) reaching out to customers and other partners to offer new and innovative responses to a wealth of new system and customer data.

Some notable examples include Consolidated Edison and Orange & Rockland in New York, Arizona Public Service, CenterPoint and Oncor Texas utilities, and others around the country.

This spectrum of customer relationship management is exactly that—a spectrum. There are traditional utilities investing in advanced customer experience capabilities and utilities in competitive states still managing to the J.D. Power benchmark. There are innovative utilities in most jurisdictions and multi-jurisdictional utilities that are balancing these choices in multiple ways.

The utility customer relationship maturity model: Four phases of progress

Utilities’ legislative and regulatory environments vary greatly, and their customer bases are far from homogeneous. But together, these factors create an energy economy that influences a given utility’s business objectives as well as the customer relationship strategy it employs to achieve those objectives. The traits and characteristics of a given energy economy also impact the value proposition of a utility’s investments in customer service.

Our examination of many utilities across the United States and their associated energy economies reveals a continuum of business goals and the degree of maturity of their customer relationship strategies. The Utility Customer Relationship Maturity Model outlines four distinct phases of progress for utility business goals and associated customer relationship strategy, based on a utility’s unique energy economy.

Utility models range from a traditional utility whose supply chain is entirely vertically integrated to a customer-centric organization relentlessly focused on providing competitive customer experiences. A utility’s business goals and customer relationship outlook help determine where on the maturity continuum the organization currently resides (or wants to reside). As previously implied, advancing along the maturity continuum requires strategic investment in customer service solutions that are aligned to the utility’s internal and external characteristics in order to realize value.

The following sections describe in detail the four phases of maturity, their underlying customer relationship strategies, and the various customer service solutions that make these strategies a reality. Additionally, each section describes internal and external characteristics necessary to realize benefits from various customer service solutions, to support feasibility and shape a more prudent strategy specific to a given utility. It is important to note that while this model provides a framework and a context for the choices that a utility must evaluate and make, there are no well- defined boundaries between levels; and the time and effort to cross boundaries will be different for each utility. Additionally, it is important to note that not every utility will benefit by advancing to the next maturity phase. More specifically, not every utility’s energy economy is set up to support and benefit from advanced levels of the customer relationship. The maturity model illustrates the contrast observed among utilities across the United States.

Level 1: Traditional utility

The key characteristics or traits of a traditional utility that shape its relationship with customers are that it is government-lead and vertically integrated across the energy supply chain. As for its leadership, risk-averse state legislatures tend to be less progressive with respect to clean energy, tax subsidies, and competitive alternatives. A traditional utility’s workforce, therefore, is unlikely to have undergone significant change and developed new competencies. The traditional utility’s emphasis on maintaining the status quo is cemented by its monopoly and the fact that customers cannot choose to take their business elsewhere. A traditional utility therefore has little incentive to focus on customer service.

The traditional utility and its conventional energy economy focus on providing safe, reliable, and affordable service to consumers. Investments in enhancing customer relationships are reactive and address broken or aged processes and/or rising customer complaints. A traditional utility’s typical customer service activities include common utility customer life-cycle interactions: initiate new service; bill for service; collect and credit payments; manage usage; restore outages; respond to questions; and stop service. In these utilities, tools, processes, and technologies, however, derive from function and business needs rather than customer perspectives or needs. For these utilities, customer needs are often dictated or mandated by legislative and regulatory bodies on the customers’ behalf.

In this phase of maturity, utilities are balancing investments in aging infrastructure with replacing home-grown customer service systems. Typically, feedback in the form of annual customer satisfaction surveys and third-party surveys provide overall glimpses of customer frustrations or gaps in services. It is not unusual, though, for these feedback mechanisms to be influenced by singular events such as a major storm, a rate increase, or unfavorable press coverage.

Utilities in this phase are improving their responses to customer issues, investing in longer term reliability and operations improvements, and generally trying to control the cost and quality of their basic services while managing regulatory mandates. They are focused on the basics of safe, reliable, and affordable electricity.

The decision to invest in new customer service technologies and processes occurs when current systems (such as a customer information system or interactive voice response platform) are no longer supported or when new processes (such as an outage management system or work management system, or an upgrade or changes to the call center) offer significant operational efficiencies. A combination of regulatory, operational, and overall satisfaction drivers, as well as local economic development support and community involvement, influence the level and pace of a traditional utility’s investment in customer experience.

For traditional utilities and their customers, these choices are important and certainly offer some improvement in response, efficiencies, and reliability while controlling the overall short-run cost of customer care and the size of the customer bill. In addition, even the traditional monopoly is starting to increase its collection and evaluation of customer feedback and respond to benchmark surveys like those from J.D. Power. As these utilities increase customer input and response, they begin to leverage the opportunities and benefits available in the next step up in customer service maturity: the customer-aware utility.

Level 2: Customer-aware utility

Utilities in many states are now facing investment choices beyond the basic operational, reliability, and customer satisfaction investments of a traditional utility. Often, these are the result of external impacts such as increased regulatory mandates for energy efficiency or demand response; legislative directives and subsidies for clean energy and rooftop solar; and customer expectations of increased choice, mobility, speed, and self-service capabilities.

Responding to these drivers has broadened utility investment mechanisms such as business case analysis, risk analysis, and process improvements to directly include the customer perspective.

Utilities recognize that reducing customer frustration and simplifying the complexity of key transactions can also reduce operating costs. If it is possible to narrow the “funnel” of issues that drive customer complaints and confusion, then it is also possible to reduce the resources required to respond to complaints. If a utility can motivate customers to use self-service tools, then it can redirect internal resources to other activities. If the utility provides customers with easy access to their own information, upcoming activities, and outage status, then it has created true customer value. Finally, if the utility educates and arms its customers with the right information and tools, then it can integrate energy management, energy generation, and even energy storage choices with utility planning and operations to produce mutual benefits.

Customer-aware utilities balance key business goals of operational excellence and reduced operations and investment expense with customer goals of controlling their energy costs and staying connected. Customer “satisfaction,” then, derives from improved customer experiences and not just a set of static benchmarks. Customer benefits and a wider range of choices now enter the investment discussions.

Utilities in this phase have reached beyond regulatory-mandated customer response to a more engaged and inclusive customer involvement process. Many have introduced “voice-of-the-customer” programs as listening posts and to gather information for driving technology decisions and priorities. Surveys provide insight into customers’ preferences for communication channels, payment options, and hours of service. In addition, customer-aware utilities are starting to provide their customers with increased technological support and minimal digital enhancements that drive down operations expense, such as e-bill, e-pay, and intelligent IVR capabilities. These utilities are also investing in new web designs that offer easier access – especially during storms. Outage communications, restoration status, and real-time outage maps available through mobile platforms can greatly ease customer anxiety, reduce calls during restoration periods, and increase confidence in the utility’s efforts to get everyone back on-line.

Utilities in this customer-aware phase invest to manage external factors such as legislative incentives for renewable and distributed energy, regulatory focus on improved outage response, and increased customer demand for information and choice. New customer-aware investments, while not insignificant, focus more on communications, feedback, and information exchange. They also can drive down operating costs and create customer goodwill. A utility realizes full benefits of these investments when it is ready to go beyond regulatory minimums and invest in both technologies and training for employees to better serve customers. These investments also demand a healthy dialogue with local regulators and a receptive audience for the increase in investment. Finally, utility leadership must also understand and support the necessary investments in improving customer experience, as once a utility has started this journey it raises the expectations of all its stakeholders.

Level 3: Customer-focused utility

As a utility begins to add customer service capabilities and prioritize the customer perspective in its day-to-day business operations, it moves toward becoming a “customer-focused” utility. As noted earlier, the boundary between these two phases is dynamic and affected by many factors, including state-level and utility-level traits, pace of change, and appetites for risk. While most of the utilities in this phase have significantly progressed in their inclusion and valuation of customer expectations and trends, some utilities in the “customer-aware” phase have also begun to make the same type of investments in systems such as automated meter infrastructures (AMI), processes such as customer journey mapping and customer effort evaluations, and technologies such as social media and digital experiences.

The most important distinguishing factor for utilities in the customer-focused phase is a desire to develop a deep understanding of customer needs and build a new relationship.

Utilities arrive at this stage through many paths, balancing internal and external drivers and mandates. The unifying attribute of these utilities is a robust, holistic, and well-articulated customer strategy. This strategy defines a “brand promise” designed to benefit all stakeholders: customers, employees, leaders, regulators, and stakeholders. The strategy includes guiding principles for prioritizing improvements, new services, and investments. It also includes an integrated set of operational and customer experience metrics that is much broader and more actionable than the typical utility benchmark surveys. Finally, the strategy recognizes the value and sustainable nature of improved customer focus, and this perspective permeates the enterprise.

In this phase, customer service investments and solutions are more significant; they impact the entire organization and not just the customer service department. Transformational investments may include AMI telecommunication and meter systems; dispatch and substation automation investments; improvements in key customer transactions and “moments of truth”; upgraded work management and outage management capabilities and tools; integration of distributed energy resources into operations and dispatch functions; and capabilities for gathering, integrating, and analyzing data to inform planning, operations, maintenance, outage restoration, and customer choices.

A voice-of-the-customer program that started in the customer-aware stage now matures into a robust and diverse set of outreach and feedback initiatives that drives transparent decision-making. Ongoing customer journey mapping evolves into an integrated Lean Six Sigma framework, linking performance improvements with both customer and operational targets. The utility uses design- thinking methodology — a concept employed in competitive markets to explore and experiment with new offerings and solutions — to develop and deploy new services. In many cases, a full- scale digital self-service strategy embraces all platforms, including web, mobile apps, and social media, to inform customers and glean key decision-support information. Associated analytics programs and activities grow into a value-added role, integrated into the utility’s planning and operations systems as well as customer experiences.

In this phase more than the first two, utilities need the active support and financial approval of their regulatory partners. Often, this relationship has not evolved as fast as the utility’s customer perspective; however, the value of being a customer-focused utility also accrues to regulators and state legislators. The utility will now embrace and integrate the multiple and separate mandates that occur when driven by special interests and dynamic politics. The opinion and day-to-day preferences of customers will achieve parity with state policy and federal goals. Increasing customer choice and control while also increasing operational efficiencies and accountability benefits all parties to the regulatory compact.

Change readiness, acceptance of new models, and support for innovation and expanded utility services also form a continuum. Each utility must evaluate the level of risk and reward this customer-focused model offers and proceed accordingly. New regulatory models, business models, and customer expectations are difficult to align, and the decision cycles in this model are long and complicated.

Many utilities, including municipal utilities, are proceeding down this path. They are investing in AMI systems with support from federal grants and state rate recovery. They are investing in new workforce capabilities and training. They are creating integrated customer strategies and deploying technology roadmaps. These initiatives may be ahead of, behind, or in synch with the regulatory process, but their message is consistent and their strategy is transparent—they are adapting to the new clean energy economy and balancing multiple moving parts. And the two most important stakeholders in this equation, customers and employees, are in lockstep with this focus.

Level 4: Customer-centric organization

The goal of full marketplace competition for electric services may not seem realistic; however, there is no doubt that legislative, regulatory, and customer pressures have changed the monopoly model and will continue to erode opportunities for its growth and revenue. Some states and utilities have recognized the opportunity for further changes and are in the process of evolving toward a new future state. The most notable example of this transformation is that of utilities in New York. There, regulators and legislators are mandating that utilities plan and change how they operate their distribution system —that they start accommodating all providers of energy and services across the integrated distribution system platform. The utility role in this new platform is still evolving. Some New York utilities have decided that such a future requires an organizational commitment to customers and other partners. They are devising processes, creating organizational roles and structures, and defining performance metrics that are customer- centric, not asset-centric.

This “customer centricity” is more the hallmark of competitive retail organizations like Nordstrom, Neiman Marcus, Apple and Amazon, than of regulated utilities. In some states, however, utilities such as CenterPoint, Oncor, and Pepco are already limited to managing only the distribution system and delivering the energy of other firms to end customers. Operating in this capacity intensifies focus on customer perspectives.

In other states, the risks and changes in the asset-intensive nature of carbon-based fuels, aging infrastructure, and transmission system operators have caused utilities to rethink their value proposition and focus more on customer opportunities. Finally, states with very active rooftop solar and distributed energy plans are also forcing a change in the utility mind-set and strategy to seek a customer value proposition that can replace years of level or no growth with sales and services in new, non-traditional ways.

Regardless of the drivers, utilities that reach this level will have proceeded through the customer- aware and customer-focused phases and expanded the customer influence and impact on their organization. Our analysis did not identify any utilities currently at this level, but we observed movement and trends that point in this direction.

The customer-centric organization becomes successful by sensing, influencing, and meeting customer expectations. ”

For instance, utilities are now deploying robust customer strategies and investing in new workforce skills and capabilities. The role of Chief Customer Officer is no longer rare in the utility hierarchy, and new customer-centric organizations that encompass more than the traditional customer operations departments are beginning to appear. Industry awards recognize customer marketing, communications, and engagement. The advent of customer collaboration organizations, the deployment of AMI meters, and the expansion of distributed generation require utilities to integrate many new customer perspectives into their planning.

The customer-centric organization becomes successful by sensing, influencing, and meeting customer expectations. We have seen more movement towards training customer service representatives to help customers make confident choices around energy efficiency, new appliances, and even distributed energy alternatives. Utilities with a positive brand image can often leverage this into an advisory role. Over time, and with the continuing evolution of data collection and analysis, this relationship could evolve into “Amazon-like” customer data mining and trend analysis capabilities that produce new services and revenues.

A customer-centric utility will have an organizational commitment to customers, and customers will have a presence in all major decisions. Planning, operations, maintenance, and outage response will take on a customer flavor, in addition to system and safety elements. This integration of customer perspectives will deliver unexpected benefits and alliances, as well as drive down costs and create new opportunities for brokered customer data and third-party services.

The customer-centric utility will reorganize to break down silos and operate more like a competitive organization, putting customers first and communicating as “one” company with strong governance over communications, digital technologies, and data management.

The customer-centric utility will also identify and evaluate new customer solutions, especially around competitive or non-traditional services. New value-added and revenue-generating services may include support for distributed generation, options to buy new energy management or demand response technologies, and/or partnerships with electric vehicle, charging, and battery storage companies.

This new regulatory environment is the greatest barrier we see today to moving the industry to a customer-centric model. ”

The customer-centric utility will leverage all of the communications, data collection, feedback, and customer experience analyses and technologies described in the previous phase. Moreover, the new organization will use that data and feedback to cut across utility silos and create integrated and accountable plans, campaigns, and metrics. It is likely this organization will use more advanced systems such as a customer relationship management (CRM) and advanced distribution management (ADMS) system, to merge customer and system data. It also will have strong multi- function data analytics, management, and reporting capabilities that track performance, identify new opportunities, and align business units.

These investments and changes will require strong regulatory support and a new regulatory paradigm that recognize innovation and brand recognition. Utilities will be allowed to compete for end-use services. And regulators will re- balance the risk and benefits for stakeholders.

This new regulatory environment is the greatest barrier we see today to moving the industry to a customer-centric model. Only in New York has this dialogue translated into new models and metrics.

Conclusion

This paper provides a model and some insights as to the choices and activities required for increasing the value and strength of utilities’ customer relationships. In presenting this model, we acknowledge that some utilities might already be at the right level of the Utility Customer Relationship Maturity Model given their regulatory and customer attributes. With such diversity across the country in business structures and regulatory mandates, there is no reason all utilities need to be in the “customer-centric” mode to succeed. In fact, many utilities will produce new value and do well as a customer-aware or customer-focused organization.

The differentiating attributes and elements can blend together at the edges, allowing for variations in timing and depth of solutions as well as the diversity of regulatory environments. It is apparent, however, that utilities will not simply wake up one morning and be “customer-focused.” The investment and commitment required to move away from the traditional model requires leadership intent and inspiration.

Those utilities facing the market and customer challenges we explored can use this model to develop a roadmap for balancing the necessary organizational changes and investments with the relevant drivers at any time in their plan. Utilities can prioritize investments for current needs and plan for future opportunities. They can hire, train, and manage employees to meet customer needs as well as system needs. Systems and technologies can produce customer value and improve operating efficiencies. The key here is to bite off only as much as the utility can swallow. Too much investment in customer relationship management can over stress and overwhelm employees. Investments that are too advanced or robust can also make it difficult to gain regulatory support.

An appropriate level of customer, employee, regulator, and third-party engagement will be key to success. Matching a utility’s business model and drivers to the readiness and expectations of its customer base is only possible when the utility listens to and involves its customer base. From there, calculated innovation will help a utility manage risk and prioritizes investments. The Utility Customer Relationship Maturity Model provides a basis for understanding where a utility has been and where it is going.