June 2018 | Report

Addressing Watershed Fragmentation Through Data Collaboration

Water utilities are now tasked with finding solutions to the social, environmental, and economic issues causing these complications

Addressing Watershed Fragmentation Through Data Collaboration

In light of escalated water issues over the past few years – from flooding to drought to poor quality – water utilities are now tasked with finding solutions to the social, environmental, and economic issues causing these complications.

But these are large-scale, underlying issues which require focused planning, funding, and collaboration among multiple water stakeholders, not just utilities. One critical barrier to this collaboration is the fragmentation of our watersheds.

This paper explores the shortcomings of watershed governance, data collection, and collaboration, coupled with recommendations on how they may be improved to reduce watershed fragmentation.

Why is watershed fragmentation a problem?

Our current paradigm for managing watersheds is to draw boundaries around political jurisdictions, and build infrastructure that fits the convenience of demographics, rather than following the natural boundaries that define watersheds.

As water moves from a natural water body to urban infrastructure, it flows from the source to a purification process, to the end user, then passes through a drain and into a collection system, and reclamation for eventual discharge back into a water body. This hydrologic process, which is a contiguous set of pipes and flows, is managed by a multitude of agencies ranging from environmental, to utility to public health, and each follows a myriad of local, state, and federal regulations.

At the federal regulatory level, the single system is split in half via the Clean Water Act (CWA) governing source water and effluent, and the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) governing the water we drink. While this is logical from an ease of management perspective, it can create a great deal of inefficiencies and competing priorities. Consider that the SDWA encourages the use of orthophosphate to protect against lead pipes, while the CWA mandates the removal of phosphate from the effluent.

In the City of Chicago, there are 12 different agencies responsible for managing water resources representing local, state, and federal levels. Despite, or perhaps due to this cast of characters, neither the water utility nor any other single organization can solve the major issues of water quality, scarcity, and flooding without collaboration. Yet, there is no federal structure or guidance on how water agencies can form watershed coalitions to collaborate and develop effective, holistic solutions.

This lack of unified governance creates serious problems for agencies looking to solve these larger issues. One well-known example occurred in Toledo, Ohio, in the summer of 2014 when a toxic algae bloom in Lake Erie contaminated the city’s drinking water. Nutrient runoff from agricultural activities upstream and inland from Toledo stimulated the toxic algae that formed over the city’s intake system, which pulls water from the lake. By the time the algae bloom formed and began affecting the city’s drinking water, it was too late for Toledo Water to take proactive steps to ensure water safety. This resulted in 400,000 people without water for four days, despite being on the coast of one of the world’s largest freshwater lakes.

Despite the serious consequences that chemicals from agricultural and industrial processes can have on our water supplies, runoff pollutants and water supply are regulated by different agencies depending on the pollution source. Unless we treat the watershed as the unified system that it is, with effects up and down the chain, water utilities, businesses, and citizens will have increased exposure to the consequences of drought, flooding, and poor water quality.

Fortunately, water managers from utilities, regulatory agencies, and environmental groups are beginning to are beginning to recognize the value of digital technology, the Internet of Things, and data analytics to unify fragmented watersheds. For example, smart meters and sensors are currently used to detect and manage leaks, improve billing processes, and reduce losses from non-revenue water. Now, water utilities have a growing opportunity to expand data collection to affect not only physical assets, but the surrounding watershed as well. The infrastructure for consumption metering can also be used to collect additional environmental data, helping multiple stakeholders to analyze and gain a more comprehensive understanding of the watershed. However, to realize this benefit, collaboration is needed.

How collaboration improves water management

The challenges associated with fragmentation are complex and involve many different stakeholders. Effective solutions must support end-to-end management of water usage from drinking—water production to waste—water treatment while also being holistic across stakeholders and regions. The most effective solutions will involve watershed governance, data collection, and collaboration.

Governance: In its current state, our water governance structure has little to no alignment with the hydrology of a watershed. For example, approximately 90% of the U.S. population is served by water utilities and/ or municipal waste. These municipal jurisdictions did not consider the geographic watershed perspective during their inception, but rather were formed to serve populations within boundaries of political or economic convenience. As a result, municipal jurisdictions have minimal control over both the watershed providing their source water and the protection of their recreational waterways. (A municipality engaged in the formation of watershed coalitions, collaborations, and joint authorities can wield a more holistic influence over the management of their most important natural resource.)

Data collection: Data collection is the core of any solution. Currently, the most widespread use of digital technology is in advanced metering solutions that combine telecommunications with IoT to measure consumption. Advanced analytics can identify if a customer has a water leak within their residence – a leaking sprinkler system, a running toilet, or a burst pipe. Utilities also use this data along with hydraulic models and asset management to detect water main leaks in the distribution system. The World Bank estimates that the world loses around 25% to 35% of water due to leakage – and this non-revenue water is worth $14 billion worldwide. Leak detection data management is a high priority for water utilities because it offers tangible financial benefits, but it is not the only way for the water industry to effectively utilize digital technology.

Measurements related to water quality and availability will be critical to understanding the current state of watershed health and ways to drive improvements. Current technology exists to monitor rain and snowfall, soil moisture, water turbidity, flow rate, temperature, and surface and well water quality. Meteorological, surface, and groundwater sensors can be deployed with telemetry to send data in near real time back to a central IT infrastructure. Data can help provide predictive insights to inform planning decisions, however these sources of data are not yet integrated across the water industry, limiting the ability to collect and effectively utilize these data sets.

A New York Times article asked to compare the use and availability of data in the water industry to the energy industry. The U.S. Energy Information Administration collects data on energy pricing, productivity, usage, reserves, and more for both fossil fuel and renewable energy sources. It then makes this information available and accessible to the public for free. In comparison, the main source of public water data from the federal government comes from the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Water-Use Science Project, a compilation of water- use data from the county, state, and national levels. However, there is one glaring problem with the USGS data: It takes four years to compile and publish. The most recent data set was published in November 2014, however information in that dataset was collected in 2010. When compared with monthly updates provided by the EIA, it is clear that the water industry’s data utilization has room for improvement.

Due to the fragmented nature of the management of water governance, the data collected is rarely shared across organizations within the watershed, limiting its effectiveness and value. The right data management tools and strategies, when combined with watershed collaboration, can ultimately lead to better decision-making and behavior changes to lower waste and consumption.

Collaboration: Gaining meaningful insights from disparate sources of data will require collaboration among stakeholders. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, there are over 52,000 “community water suppliers” and more than 10,000 wastewater agencies in the United States. Furthermore, there are stormwater agencies, sewer collection agencies, and dozens of organizational structures to manage impervious areas which drive stormwater runoff, such as departments of transportation, planning, zoning, and more.

Beyond the sheer number of water organizations, watershed management is fragmented due to regulatory requirements. Our water systems function as a loop from source to source, but each segment is regulated independently. Alone, utilities have limited influence to solve the major water issues of quality, scarcity, and flooding. When water stakeholders act in siloes, without collaborating to share data, value decreases. Breaking down this fragmentation of watersheds and transcending regulatory boundaries will be critical to extracting real value from collected data.

Watershed collaboration in its ideal form is not limited only to water supply and treatment, but involves a variety of stakeholders such as city planning, conservation groups, universities, research foundations, and technology companies. Fostering an environment of shared data will lead to increased efficiency when preparing for and responding to system disruptions.

Ultimately, the water utility is responsible for delivering safe water to the public and therefore is at the forefront of response when these disruptions occur. Collaboration across watersheds can reduce barriers to innovation and improve decision- making and planning. This holistic planning will help water utilities minimize exposure to upstream risks, improve response to environmental events, and enhance water quality for the entire watershed. Under this collaborative model, the utility can serve as a leader in fostering collaboration between private and public entities, which all have an interest in improved watershed management.

Some watershed managers are already coming together and showing results

Across the country, water stakeholders are beginning to take steps to collaboratively solve issues associated with watershed fragmentation. These types of engagements can be beneficial for all parties involved. Shared data can provide water and wastewater utilities with additional insights into the water they are treating, which in turn allows them to better predict and mitigate risks. Data transparency among public agencies enables these bodies to better manage drought, flooding, or other states of emergency.

These types of collaborations can also lead to economic benefits. Sharing infrastructure can allow utilities to realize economies of scale, which translate into savings for their customers. Creating joint test beds for new technologies can help spur innovation and stimulate local economies. Moving toward a centralized model for watershed management will allow utilities and other public agencies to shift from reacting to issues to anticipating and addressing problems before they impact operations and customers.

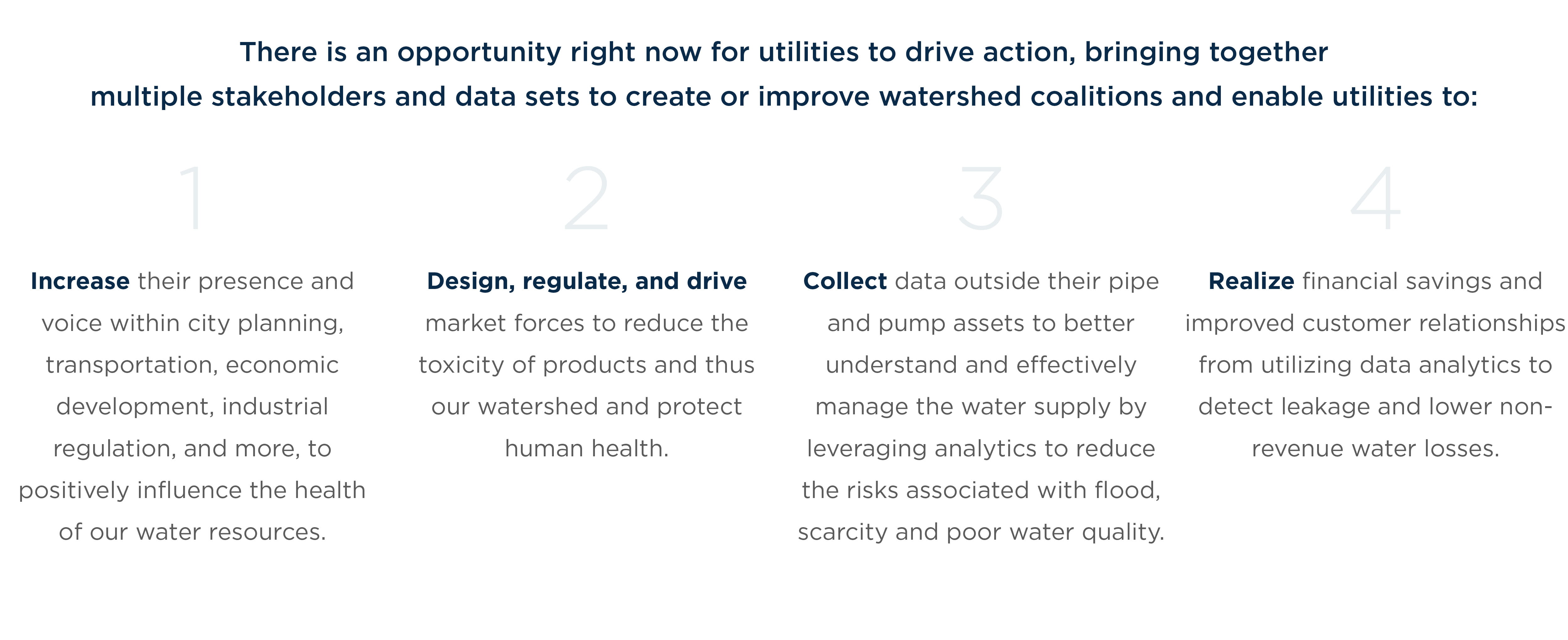

4 steps utilities can take now to improve watershed collaboration

These case studies demonstrate how watershed data collaborations bring value to water utilities, yet there is a much greater potential to improve our water resource management through data- oriented collaborations. Technology companies like IBM, Microsoft, and Infor have begun developing water platforms with early adopters of watershed data analytics such as the Southern Ontario Water Consortium and UILabs Digital City.

Today, utilities can see real world examples of watershed coalitions working collaboratively to generate a collective benefit. Water utilities are teaming with cities and farms to collectively manage water quality and increase the overall environmental health of the watershed at a reduced cost. Water utilities have an important role in solving these most fundamental societal issues – protecting our ecological integrity and human health. Utilities must expand their partnerships and collaborations with other key stakeholders to promote and improve watershed coalitions and lead the way toward higher value water services.