June 2017 | Signature Research

Software M&A Frenzy: Searching for the Competitive Edge

Get the full report

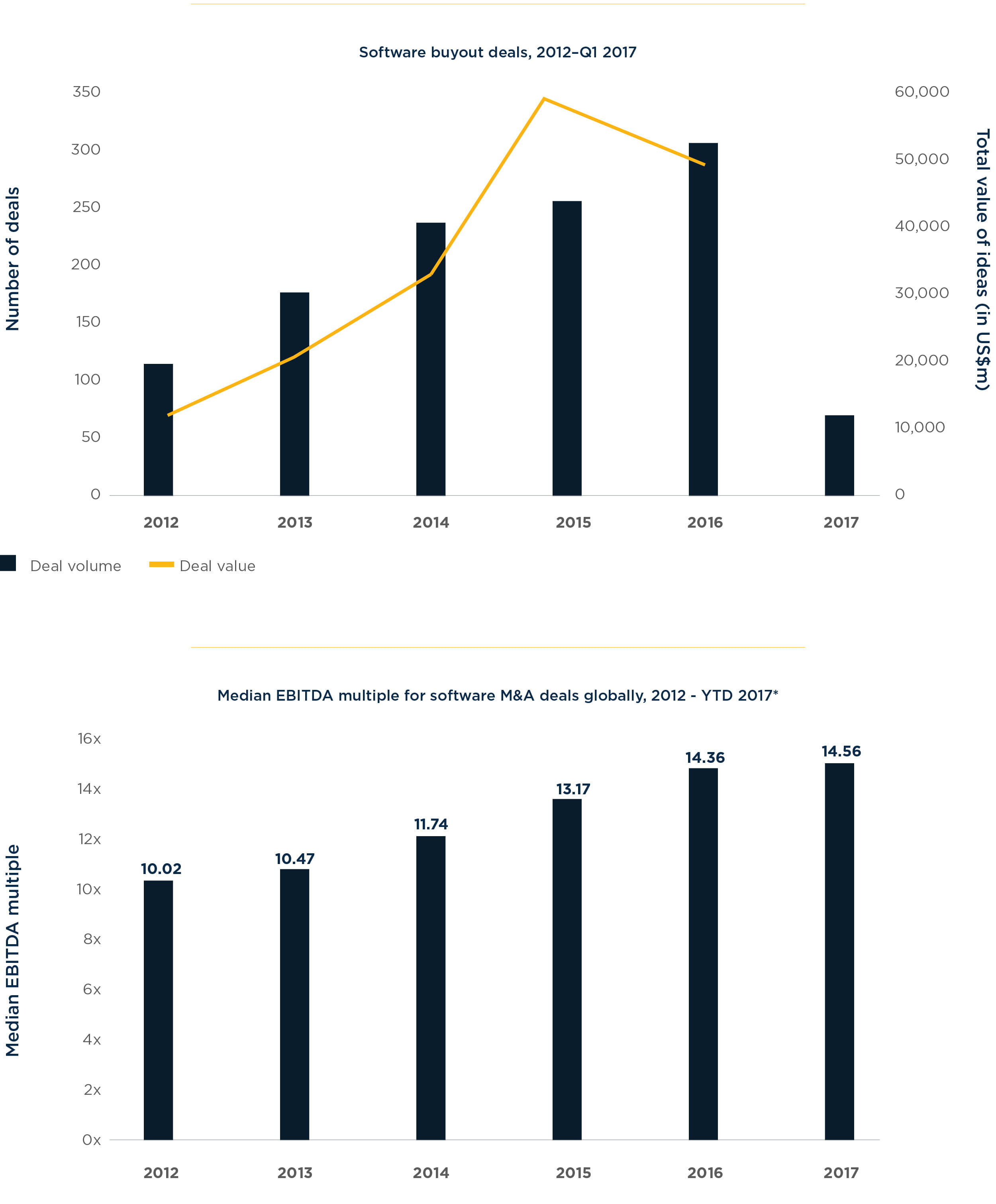

The year 2016 was a blockbuster for software M&A, with the highest number of transactions since Mergermarket records began in 1999, and overall deal volume close to a record.

Large corporate players like Microsoft, Oracle, and Salesforce spent billions on historic acquisitions. Private equity firms that once eyed the sector warily from afar raised vast sums of fresh capital and charged in, completing more buyouts than ever. Strategic investors have also looked to software investments that offer speed to innovation in increased numbers.

“We’re seeing historic levels of activity, and volumes continuing to rise,” says Mike Amiot, Senior Director in the Mergers and Acquisitions practice at West Monroe Partners. “There’s a much higher focus on software entities today that help differentiate our clients in their markets or provide them a competitive advantage.”

All this interest has spurred valuations: The tech-laden NASDAQ Composite index, which smashed its dotcom bubble peak in 2015, finished 2016 even higher and continued climbing into early 2017. Survey data presented in this report indicate this frenzied pace is set to continue.

Corporations and private equity firms have piled up mountains of cash. Slightly less than half (46%) of the US$1.7 trillion American companies held on their books in early 2017 belonged to tech giants like Apple and Microsoft. Meanwhile, in October, Japan’s SoftBank announced a new technology fund that could, with the participation of Saudi Arabia, eventually total US$100 billion. U.S. firm Silver Lake said in April 2017 it had raised US$15 billion to invest in technology.

Where will this capital be spent? This survey suggests investors are looking closely at firms with specialized, industry-specific software — especially in areas like fintech and healthcare — as well as at firms active in business intelligence and cloud computing.

Investors are more concerned with selecting the right targets than fretting over the price tag. Buyers want firms with management teams that have technical savvy, as well as business and financial acumen. Investors want firms with products that can be scaled up quickly and effectively, with tight speed-to-market capabilities and strong software development procedures.

All this competition means deals are moving faster, reducing time buyers spend on due diligence. This is evident in survey results, with investors saying more time and additional experienced personnel would help reduce risks.

With limited timelines to conduct due diligence, cybersecurity weighs heavily on the minds of investors. This survey finds greater dissatisfaction with due diligence into cybersecurity than with any operational or technical issues. More than half the executives surveyed say they have uncovered a cybersecurity problem after a deal closed.

To be sure, despite setting records, 2016 was not without headwinds. Activity in the United States fell precipitously in the fourth quarter after the presidential election. Indeed, the downturn in activity during the fourth quarter alone — which came during a moment of significant political and regulatory uncertainty — was enough to cause total deal volume in 2016 to register lower than 2015.

The data here already suggests a recovery: Deal volume rose in the first quarter of 2017 compared to the same quarter a year earlier, and survey results indicate more buying is afoot among both corporations and private equity players.

Chapter 1: Software M&A swelled from 2012 to 2017

While we saw a slight drop-off in M&A activity in Q4 2016 due to geopolitical uncertainty from the Brexit vote and U.S. elections, the median EBITDA multiples for software M&A globally shows a steady increase year-on-year from 2012 to 2017.

Chapter 2: The appetite for software M&A

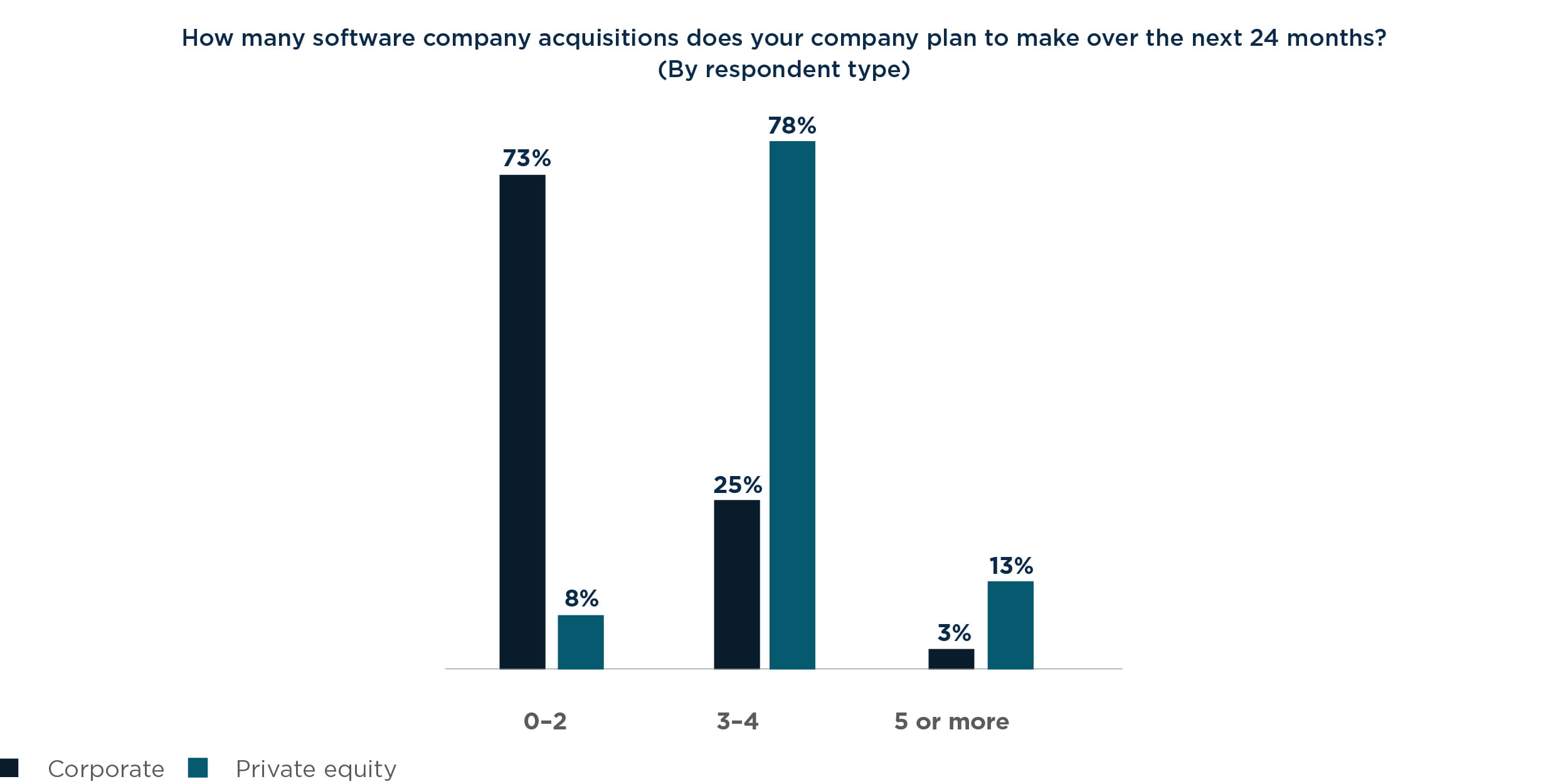

Private equity (PE) firms have pushed hard into software M&A in recent years, and survey data suggests that this trend will continue.

In 2016 we saw PE play a hand in the industry’s largest deal, with Hewlett Packard Enterprise’s (HPE) announced spinoff of its software business and the merger of those assets with

Micro Focus International for US$8.73 billion. Indeed, PE-backed volume in the software industry increased 10% in 2016, from 335 to 369 acquisitions.

Our survey results reflect this higher appetite for software acquisitions than their corporate counterparts, with 78% of PE respondents saying they expect to execute three to four deals over the next two years and 13% expecting five or more. Only 8% of PE respondents say they expect to execute two or fewer deals over the next two years.

“There is so much dry powder on the sidelines that it can be a struggle for some private equity firms to deploy capital today,” says Matt Sondag, Managing Director of Mergers and Acquisitions for West Monroe.

Among corporations, almost three-quarters (73%) say they intend to carry out two or fewer deals. A quarter (25%) expect three to four deals. Only 3% expect five or more. When combined, a solid majority (57%) of corporate and PE respondents expect to execute three to four acquisitions over the next two years.

Most buyers (82%) target mature companies — defined here as a firm with four or more years of operating experience —and a majority (52%) focus primarily on that segment. But a large minority (45%), including most corporate respondents (55%) and a sizable chunk of PE players (38%), focus primarily on younger companies with two to four years of operational experience.

“There are many younger organizations with great leadership, vision, and a strong baseline solution, but need a capital infusion to enhance their products and scale the organization. These companies are attractive to buyers who can help them scale to achieve even higher valuations,” says West Monroe’s Amiot.

Survey results suggest PE firms are more broadly interested in targets at later stages of development than corporates. Some 92% of PE respondents target mature companies and 59% focus primarily on that segment. “Investing in a mature company is less risky and adds value,” says a partner at a PE firm based in the Netherlands. A more mature company has “better developed products,” the executive says. “That makes it easier to invest and helps us get the returns we need in the long run. Investing in a mature company also gives us access to a strong management team.”

For others, however, the most important issue is the nature of the precise company in question.

“We invest in companies based on their growth prospective,” says a senior executive at a Canadian PE firm. “We analyze the returns the company has been making and the way the company will grow in the future.”

Only 3% of respondents say they focus on start-ups with less than two years of operating experience, but over a third (35%) of corporate respondents and a quarter (25%) of PE respondents say they are open to buying a brand-new company when the firm in question has what it takes to grow and create value.

“Start-ups have significant growth potential and the most effective return on investment,” says a partner in a U.S.-based PE firm. “They need to be guided in the right direction, and must have the business objectives with significant scope for growth.”

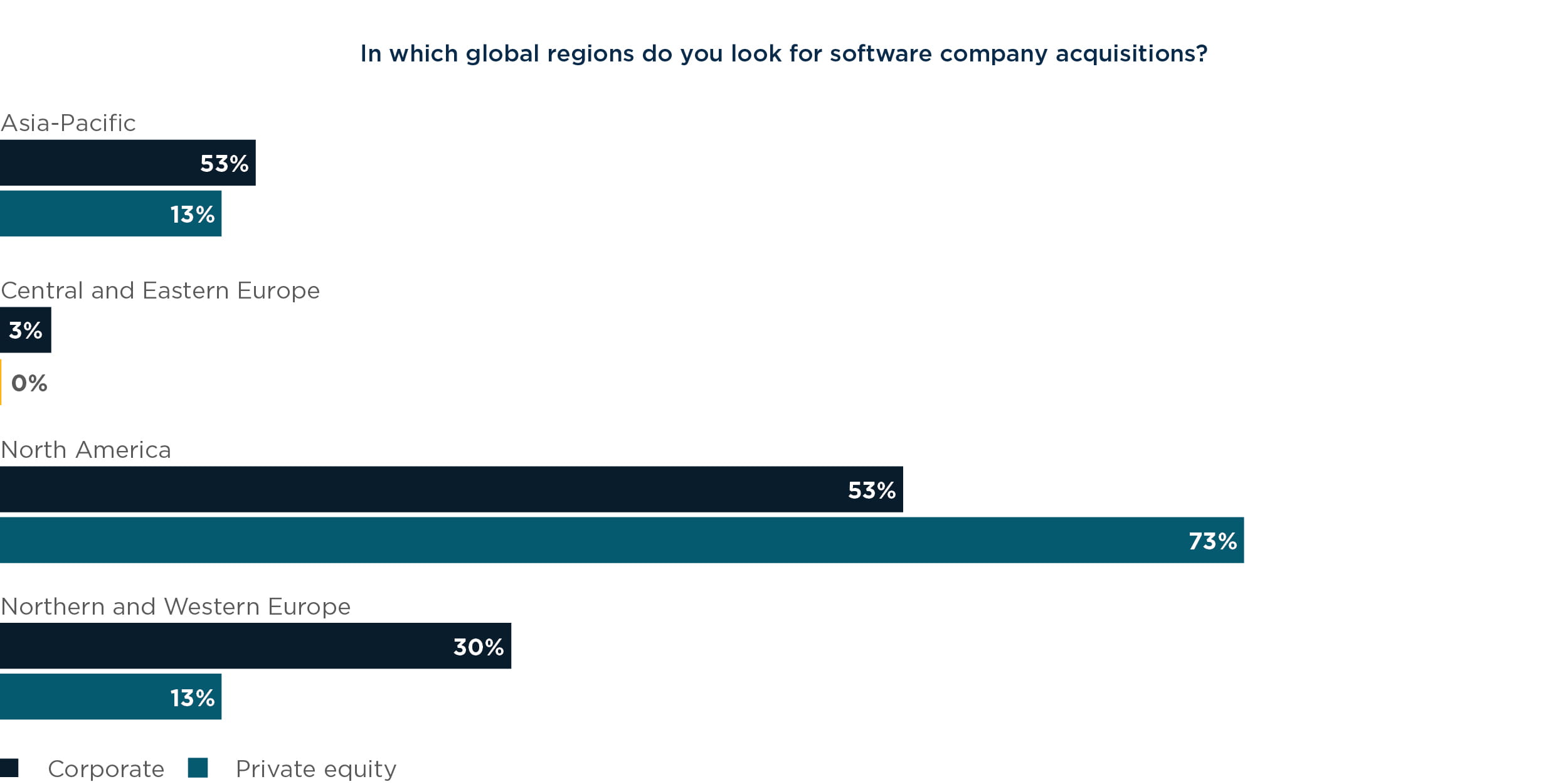

While the United States remains the top hunting ground for software acquisitions, survey results suggest buyers remain focused on their own backyards.

Among North American respondents, 78% say they primarily lookfor deals within their own region. Only 4% seek targets globally, and primarily in Europe. However, most targets again are based primarily on the asset available, their ability to scale to meet market needs, and the management teams’ business acumen.

“North American software businesses are in the leading position across the globe,” a managing director of a Canadian PE firm says. “The level of innovation, technical skills, and talents in this market are significant as many of the world’s best technology universities are (in North America).”

But the survey suggests that Asia is on the minds of many North American executives. Almost a fifth of North American buyers (18%) now call Asia-Pacific their top area of geographic interest. To be sure, some respondents say they look for deals globally — focusing on finding the right company, wherever it may be located. Among European-based firms, 85% focus on finding local deals, while 15% look primarily within North America.

“We aren’t focused on one particular region,” says the CFO of a British corporation. “We have made acquisitions across several markets in the past and they all have been equally profitable for us. It’s not the region that matters in software, it’s the technological capabilities and strengths of the business.”

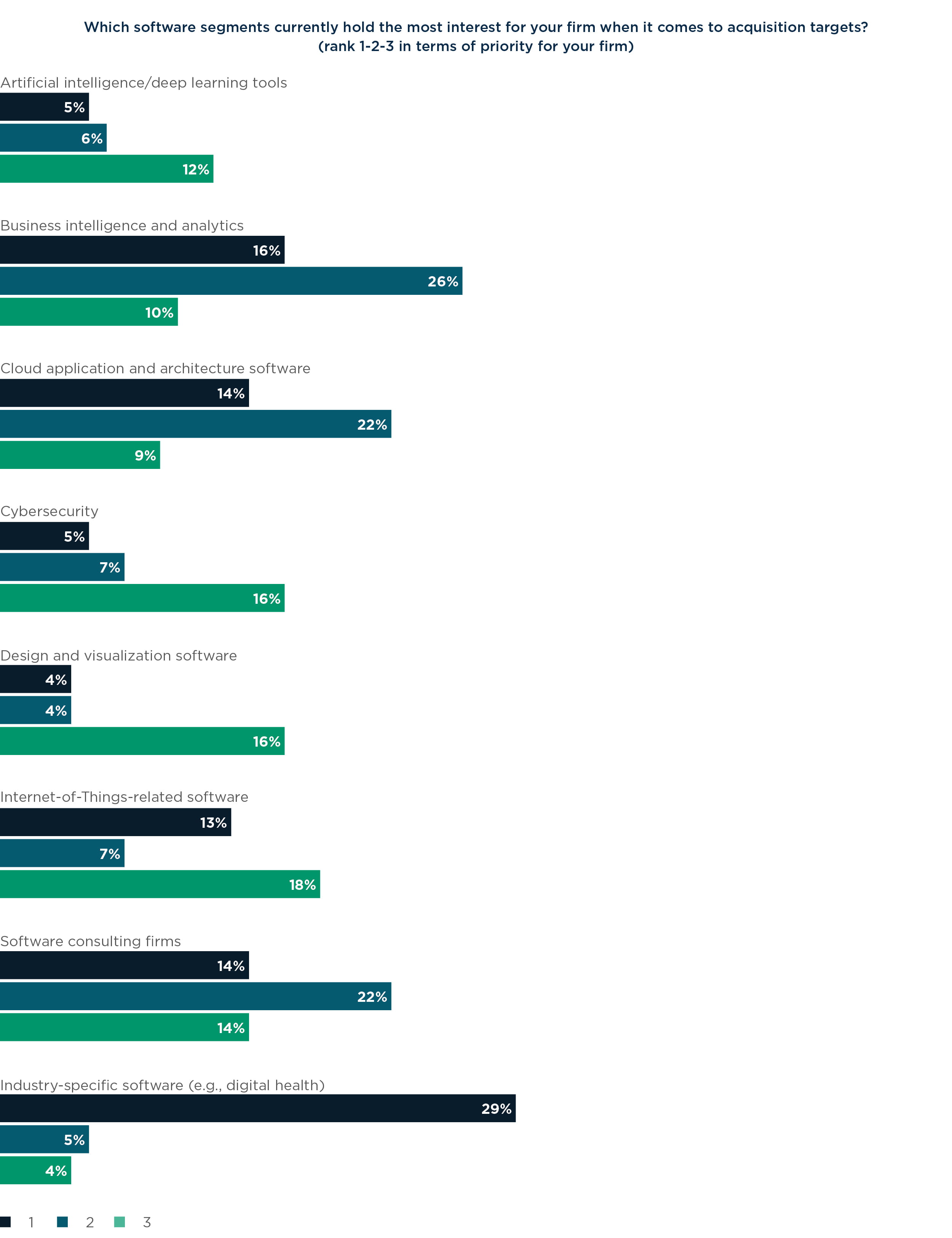

Almost a third (29%) of respondents say they are most interested in targets making specialized, industry-specific software — especially in fintech, digital media, and digital health.

Investors say they expect growth in these areas, and corporations say investing in companies making specialized products helps them innovate and stay ahead of competitors.

“We anticipate significant growth in fintech and are inclined to strengthen our position in this space through acquisitions,” says the managing director of one European PE firm. “We’ve already made several such acquisitions and are looking at potential targets that will help improve our portfolio of business service offerings to the financial sector.”

Respondents also say they’re interested in buying firms active in business intelligence and analytics, with 16% calling this field their top interest and 26% naming it as their second choice.

“Business intelligence and analytics is in great demand,” says a partner in one U.S.-based PE firm. “Companies want to be more effective and facilitate greater efficiencies in their operational and financial environments by leveraging the use of data analytics to identify new opportunities and risks. That will help them strategize and achieve higher growth.”

Corporate firms diverge from private equity investors most sharply in the segment known as the Internet of Things (IoT) — a field significantly more appealing to PE firms than to corporations.

Almost a fifth of PE firms called IoT their top interest, versus 5% of corporates.

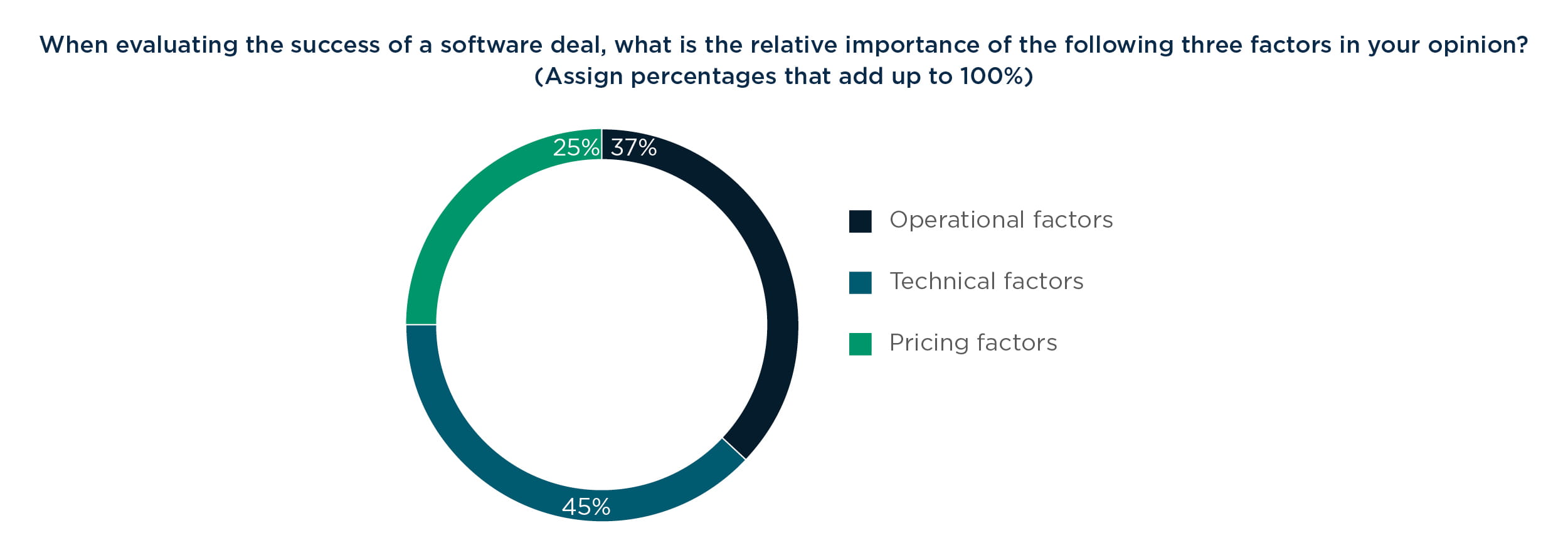

The survey suggests acquirers are focused on finding the right target — rather than paying rock-bottom prices. “There’s a search for quality in an extremely competitive marketplace. You have more funds in existence today and some of the larger funds are coming down market, especially for software assets,” Sondag says.

“You also have strategic buyers, who are typically slower to innovate, buying software assets to acquire that innovation. One example is Walmart’s acquisition of jet.com to make a move into e-commerce.”

Survey results suggest competition for the most attractive targets will be fierce. And when asked to choose the single most important factor for the success of a deal, only a quarter (25%) say price. The remainder were split between the operational (37%) and technical (38%) factors of the target.

“We are willing to pay large amounts for technologies that will help us improve efficiency, reduce costs, and develop a secure system,” says the CFO of an American network security company. “The cost of getting these technologies is not an issue.

Acquiring a company with a strong operational team, good software, capable employees, and a strong system that will help us identify threats, and discover new ways to develop our business, is very important.”

Yet buyers split evenly over whether to prioritize the target company’s technology or its business operations.

“Technology is important, but having the right operational structure and a suitable management team is more important,” says one CFO of a Canadian corporation. “The operational factors of the business must be thoroughly gauged in order to get the required synergies from the deal.”

Others say technology outweighs everything else.

“Technical factors are most important because the main motive is to acquire the technology,” says one executive vice president for corporate development at a U.S.-based corporation. “Operations can be restructured. The purchase price can be negotiated. But technical factors need to be on the mark to ensure the success of the deal.”

Chapter 3: Due diligence concerns and critiques

When it comes to due diligence, cybersecurity remains a key concern.

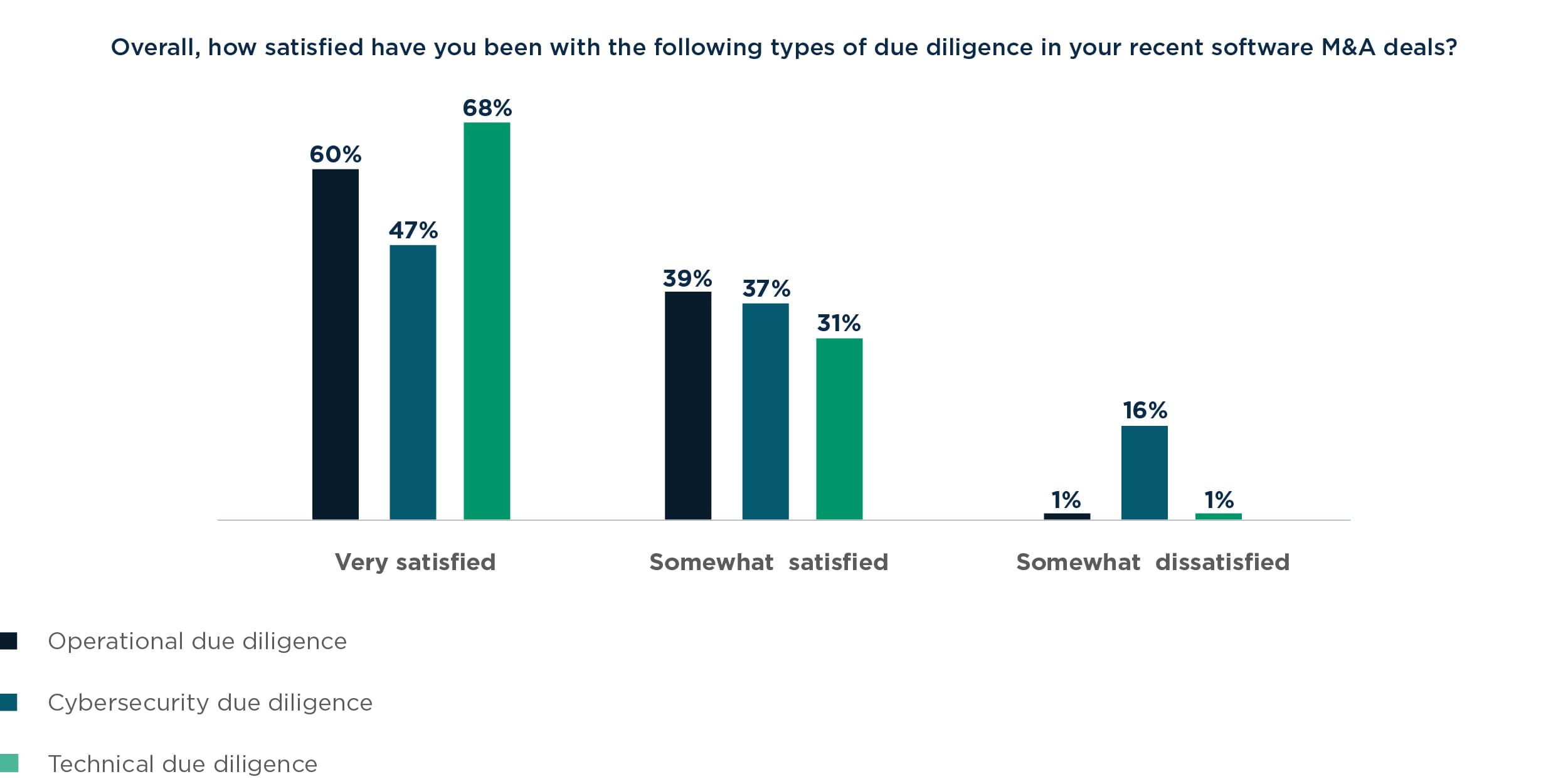

While most respondents say they’ve been satisfied with their recent experiences in due diligence, far more report negative experiences with cybersecurity due diligence (16%) than with due diligence into their acquisitions’ technology (1%) or operations (1%).

In 2016, West Monroe surveyed a diverse group of 30 senior executives at corporate and PE firms about cybersecurity due diligence and presented findings in the report Testing the Defenses: Cybersecurity Due Diligence in M&A. The results of this survey clearly show that one year later, companies are still not feeling more prepared than they were a year ago. In fact, the results of this survey would indicate a drop in cybersecurity due diligence preparedness. In the 2016 survey, only 3% were somewhat dissatisfied with their most recent cybersecurity due diligence process.

“Cybersecurity is an area of top concern for our clients,” says Sondag. “Just read the news each week for the latest breach. Fortune 100 companies are spending millions on cybersecurity, but even those companies are still vulnerable to attacks.”

Overall, 68% of respondents report being very satisfied with technical due diligence, while 60% are very satisfied with operational due diligence efforts and 47% are very satisfied with cybersecurity due diligence. Some respondents say putting time, effort, and capital into the process paid dividends.

“We have invested heavily in our due diligence team and have even hired external advisors to help us with our due diligence,” says the CEO of a British corporation. “Our due diligence was overseen with financial and technical advisors who looked into the systems of our targeted companies and gave us feedback that helped us develop our portfolio without any problems.”

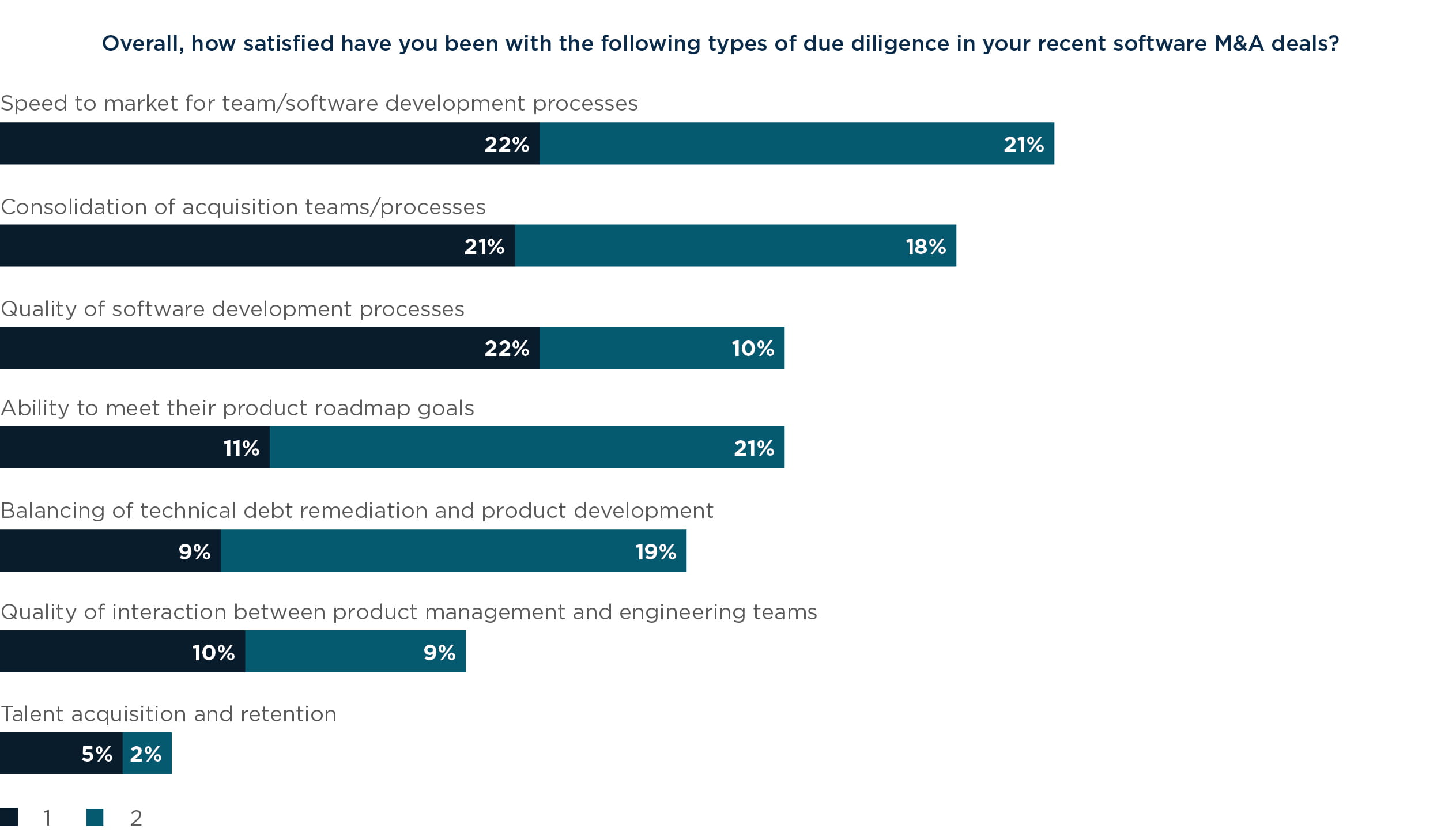

Respondents say they want their acquisitions to be operationally ready for launch, with strong software development procedures and tight speed-to-market capabilities. Indeed, those two factors

— development processes and speed-to-market — were equally ranked as top concerns (22% еаch) among survey respondents.

“We acquire companies based on the software and the services they provide,” says the CEO of a Swedish corporation. “We need to make sure the software we acquire has the potential to be developed and meet our clients’ needs. We also look at the development strategy of the software to make sure we don’t invest in any type of risk.”

After quality and speed-to-market, 21% said their top concern is consolidating the acquired team and their processes into the new owner.

“When we carry out an acquisition, we try to get access to new staff and talent,” says the CFO of one U.S. corporation. “Without the right people, we can’t execute our strategies. To achieve this, we need to make sure different teams work well with one another and communicate.”

The results underscore the importance of having plans in place to assimilate teams, processes, and cultures to achieve synergies when making bolt-on acquisitions.

“Operationally, they’re looking at team leadership, synergies, and the chemistry of the team,” says Amiot. “Similarities in these areas between the targets and existing holdings will allow assimilation of teams, vision, and leadership to be smoother and more rapid, allowing teams to focus their energy on achieving business goals and strategies.”

Among PE firms, a quarter (25%) say their second-biggest concern is finding the right balance between remediating technical debt issues and product development. Slightly fewer (23%) say their second-biggest concern is achieving their product roadmap goals.

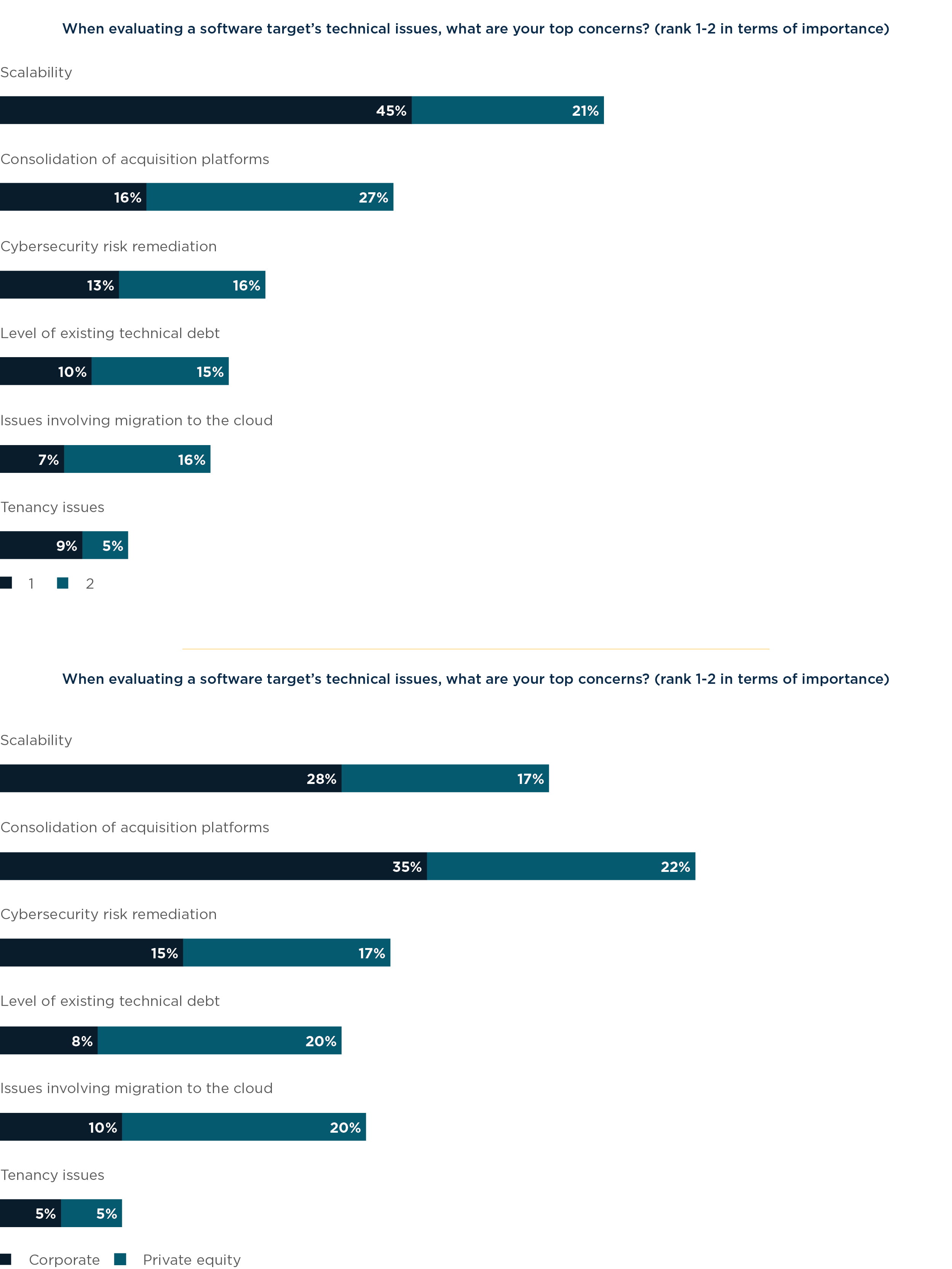

The ability to scale up the acquired company’s products and practices (45%) is by far the top concern for buyers considering a target’s technical issues.

“The company should have products that are scalable, can be developed, and have a lot of scope to grow so that our returns are not negatively affected,” says a partner for a PE firm based in Denmark.

Concerns about scalability are followed by the related issue of consolidating the acquired software platforms into a single Software as a Service (SaaS) offering, which 27% of respondents call their No. 2 concern.

“Evaluating the target’s technology leases and access points are critical during an acquisition as it can threaten the objectives of our growth strategy, exposing it to competitors and several market risks that can disrupt our growth intentions,” says the CFO of a Canadian corporation.

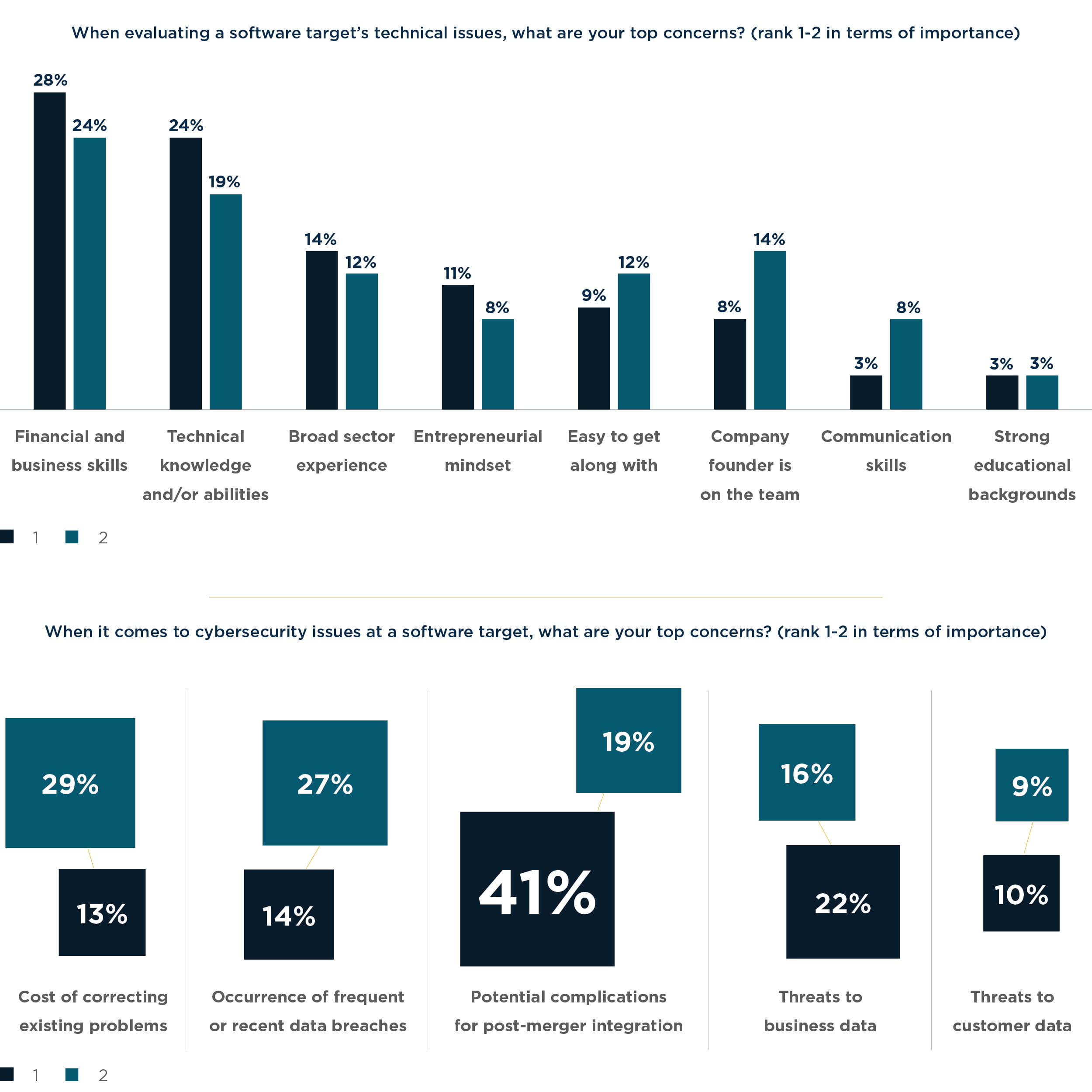

When it comes to assessing a target company’s management team, buyers say the basics matter most: Executives need to know their business, and understand their technology.

Those fundamental criteria alone accounted for almost half of respondents’ top concerns about target company management. More than a quarter (28%) say the team’s financial and business skills are the No. 1 concern, while slightly fewer (24%) say technical knowledge is the key issue.

“The target management should have end-to-end knowledge of the scope of their own technology,” says an executive

vice president in charge of corporate development at a U.S. corporation. “They should possess the required talent and abilities to facilitate growth. And they should also be very aware of the possible threats and risks that are likely to make the technology or software platforms obsolete.”

Beyond those basic business and technology issues, 14% of respondents say they focus most on finding executives with broad sector experience.

Cybersecurity weighs heavily on the minds of executives conducting M&A in the software space. Indeed, the most anxiety appears to come after the deal is done. Two in five respondents name problems during post-merger integration (41%) as their main worry when thinking about issues related to cybersecurity.

“It’s been said that there are two types of companies out there — those that have been hacked, and those that have been hacked and just don’t know it yet,” says West Monroe’s Sondag. “On average, it takes companies eight to nine months to even find out that they’ve been breached.”

Survey results indicate the issue continues to be a widespread problem. In 2016, the disclosure of two large data breaches at Yahoo in the lead-up to its acquisition by Verizon knocked US$350 million off the sale price, delaying the closure of the deal. It was a reminder of the risk every M&A transaction faces.

“The complications we face when merging systems is a major threat,” says the chief strategy officer of a German corporation. “When integrating systems, we face the risks of corrupt and incompatible files, which can have a major impact on our systems. These problems can lead to a lot of complications, which are not easy to deal with and can leave us vulnerable to hackers. It also puts us at risk of losing information.”

A fifth of respondents say their top cybersecurity concern is threats to business data. A senior vice president for corporate development at a U.S.-based corporation explains that a threat to business data is a threat to clients and customers. “It has the power to damage our reputation and push our business towards closures, being pressurized by the lack of trust displayed by the customers in commencing future dealings with us and our software platforms.”

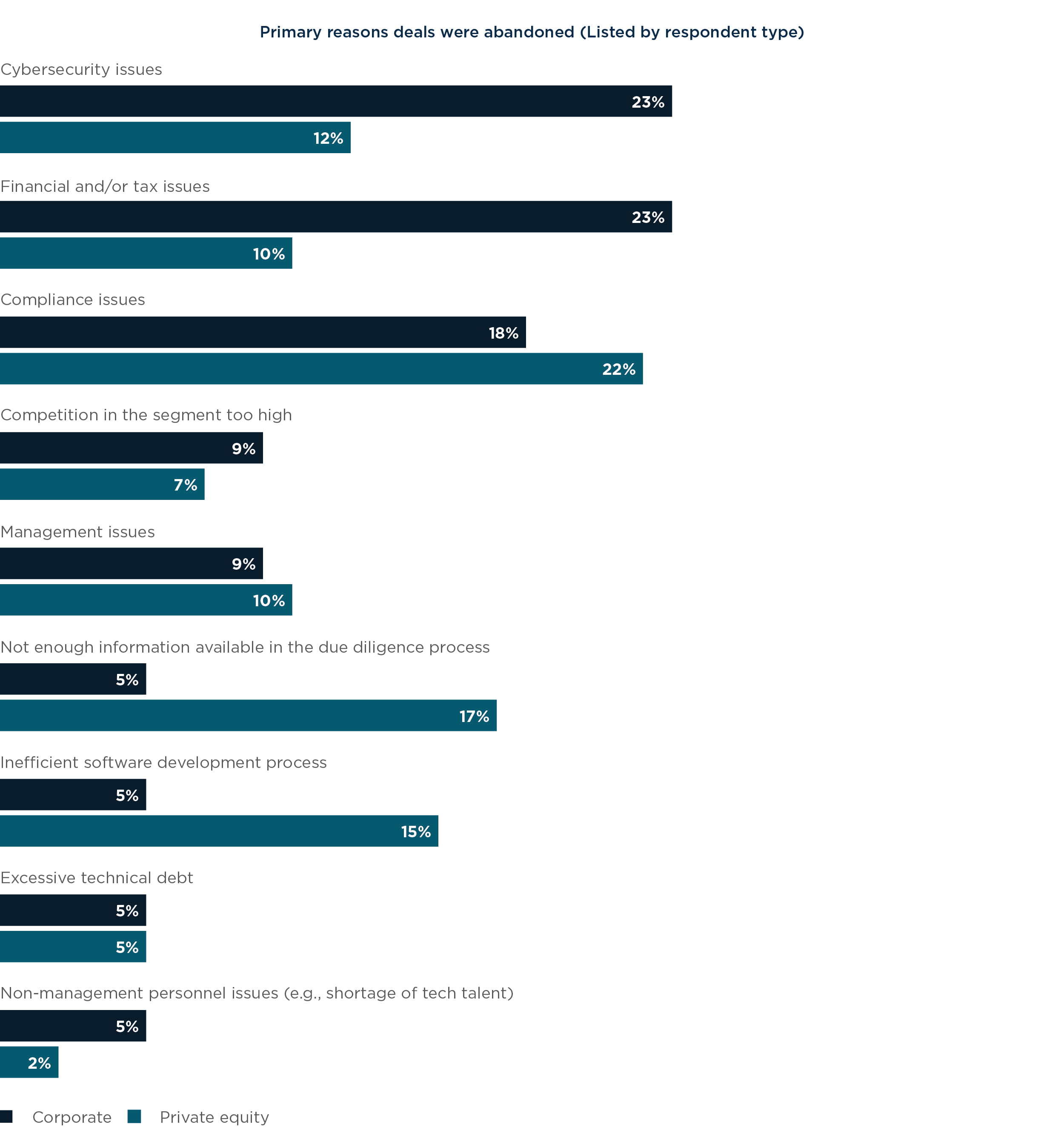

A majority of respondents (63%) say they’ve walked away from a software deal in the past, including more than half of corporate respondents and over two-thirds of PE firms.

This comes as little surprise considering that in 2016, failed deals in the United States set a record, with some 59 deals worth US$463 billion in withdrawn M&A in H1 alone. For the full calendar year, globally, 2016 saw 1,009 deals valued at US$797.2 billion, abandoned.

Among corporations, the top three reasons that deals fail are cybersecurity concerns (23%), financial and tax issues (23%), and problems with compliance (18%).

Almost a quarter of PE firms say compliance issues are the biggest deal-breakers (22%). But other PE players say the top reasons they’ve walked away from the table are difficulty gathering information during the due diligence process (17%) and inefficient software development procedures (15%).

“There were deals that were too good to be true, and once we started the due diligence process we realized that the companies had a lot of issues,” says the chief strategy officer of a German corporation. “They had underdeveloped cyber-risk systems and a lot of financial problems.” To make matters worse, says the executive, “The management was also not very easy to work with.”

Managing compliance issues can be an especially thorny task in cross-border acquisitions.

“In a couple of cases we stopped and exited halfway through the deal because not enough information was available,” says the CEO of one U.K.-based corporation. “That’s one of the main reasons we’ve exited. We have also faced problems from cyber threats when developing cybersecurity systems was too costly. One company we wanted to invest in was not compliant with all the rules and regulations in the market.”

The enforcement of new European General Data Protection Regulations (EU GDPR) in May 2018 only adds to the pressure. The fines issued under the new EU GDPR regulations are far steeper than current regulations, forcing companies into compliance. This will affect not only European acquirers but also cross-border buyers from other countries looking at targets with staff and/or customers in Europe.

This regulation change comes amid a plethora of privacy and data security regulation across the globe that must be considered when preparing for a cross-border software deal. In the United States, for example, there are 20 sector-specific national privacy or data security laws and hundreds of laws among its states and territories. In California alone, there are 25 state privacy and data security laws.

Despite the concern and risk dealmakers face when executing a software transaction, the majority of respondents (84%) say they’ve never regretted an acquisition. For the 16% who did, however, the top reason was the high level of competition in the segment (31%).

After that, a quarter (25%) say cybersecurity was the main problem, while 19% chalk up their regret primarily to compliance issues.

“Because of the changes in regulations, compliance costs have increased,” says the chief strategy officer of a corporation based in Germany. “Dealing with these issues has been problematic. The company and technologies we bought had a significant amount of debt that added up later, especially because of tax issues that we had not analyzed before we completed the deal.”

Strikingly, more than half of survey respondents (52%) say that they have discovered a cybersecurity problem at an acquired company after closing the deal. The speed at which deals move compounds the issue, as more capital pours into the sector.

The CEO of an American corporation explains: “We carried out one deal in a rush. We wanted to get it done soon and didn’t focus on the software or the risks in integrating the software. Because of this, we faced a lot of risks from hackers and had to take our systems offline. Managing the whole buying process was not easy.”

The rising amount of capital in the sector has pushed some buyers to differentiate themselves based on how quickly they can close the deal. “The number of companies that are differentiating themselves in a sale process based on speed is at an all-time high, which is scary and shows you how competitive the market has become,” says Sondag.

Others, however, say that encountering and neutralizing cybersecurity issues is just an expected part of how they do business.

“During the integration process we come across problems that we need to manage,” says the CEO of a Swedish corporation. “Cybersecurity glitches are very common. But our team is very quick on the uptake and keeps looking for these problems. The team deals with them before they become a problem for the company.”

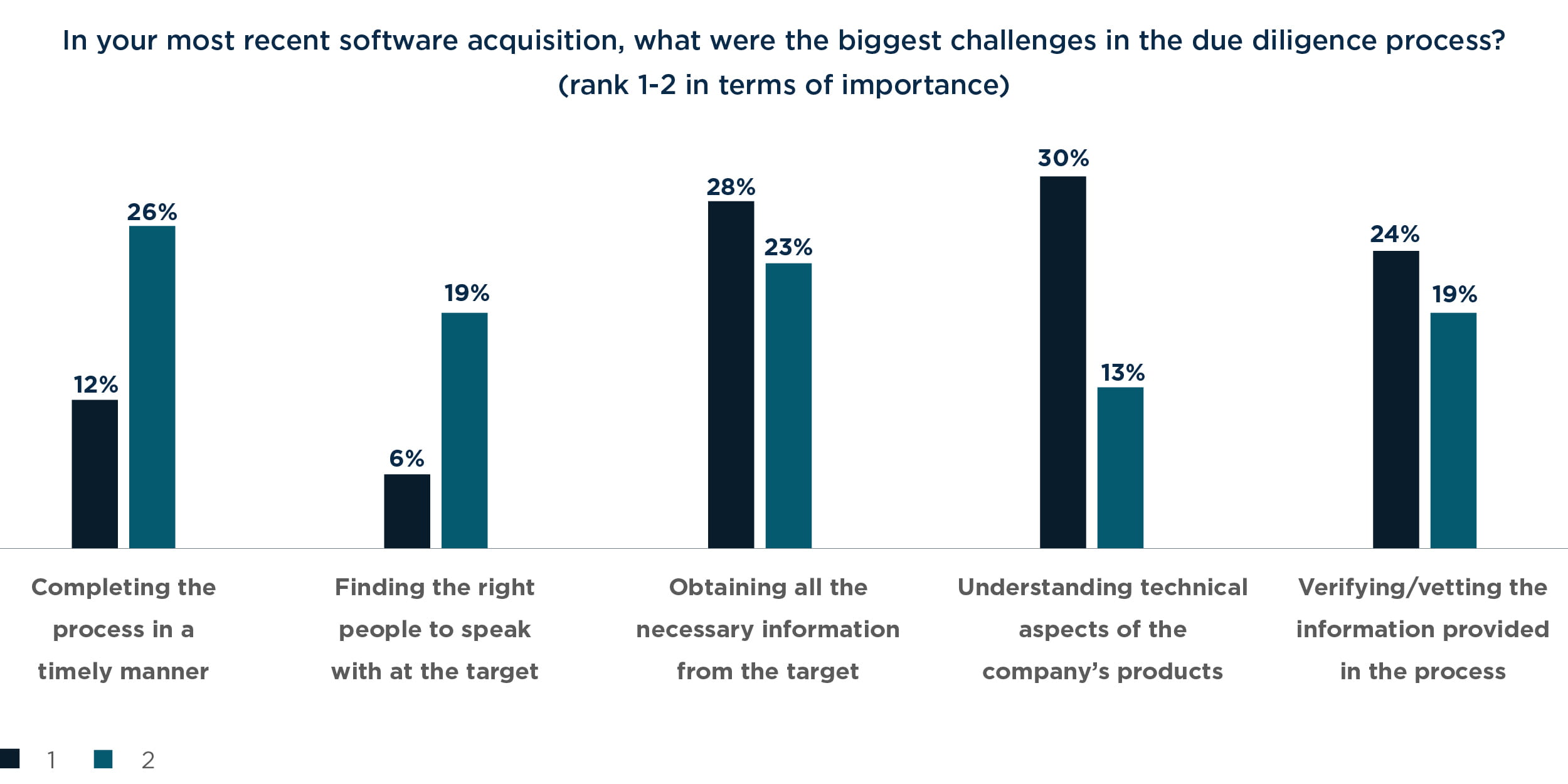

Almost a third (30%) of all respondents cite “understanding the technical aspects of their target company’s product line” as the most challenging aspect of conducting due diligence during their most recent acquisition. Some 38% of PE firms cite this as their main difficulty during their most recent buyout.

“[In one instance] we had a good level of technological understanding, but the target had a very unique structure on which they based their technology platform,” says a partner at an American PE firm. “Understanding this was a significant challenge. We did not have significant experience in that field. We got help from external technological advisors to guide us through the due diligence processes.”

Another problem is obtaining all the necessary information from the target company. Over a quarter (28%) of all respondents call that their biggest headache.

“We had problems identifying the correct people to interact with in the company to get the information we needed for the due diligence,” says the CEO of an Italian corporation. “The management was very busy. The staff was busy, too, and not very open to sharing information.”

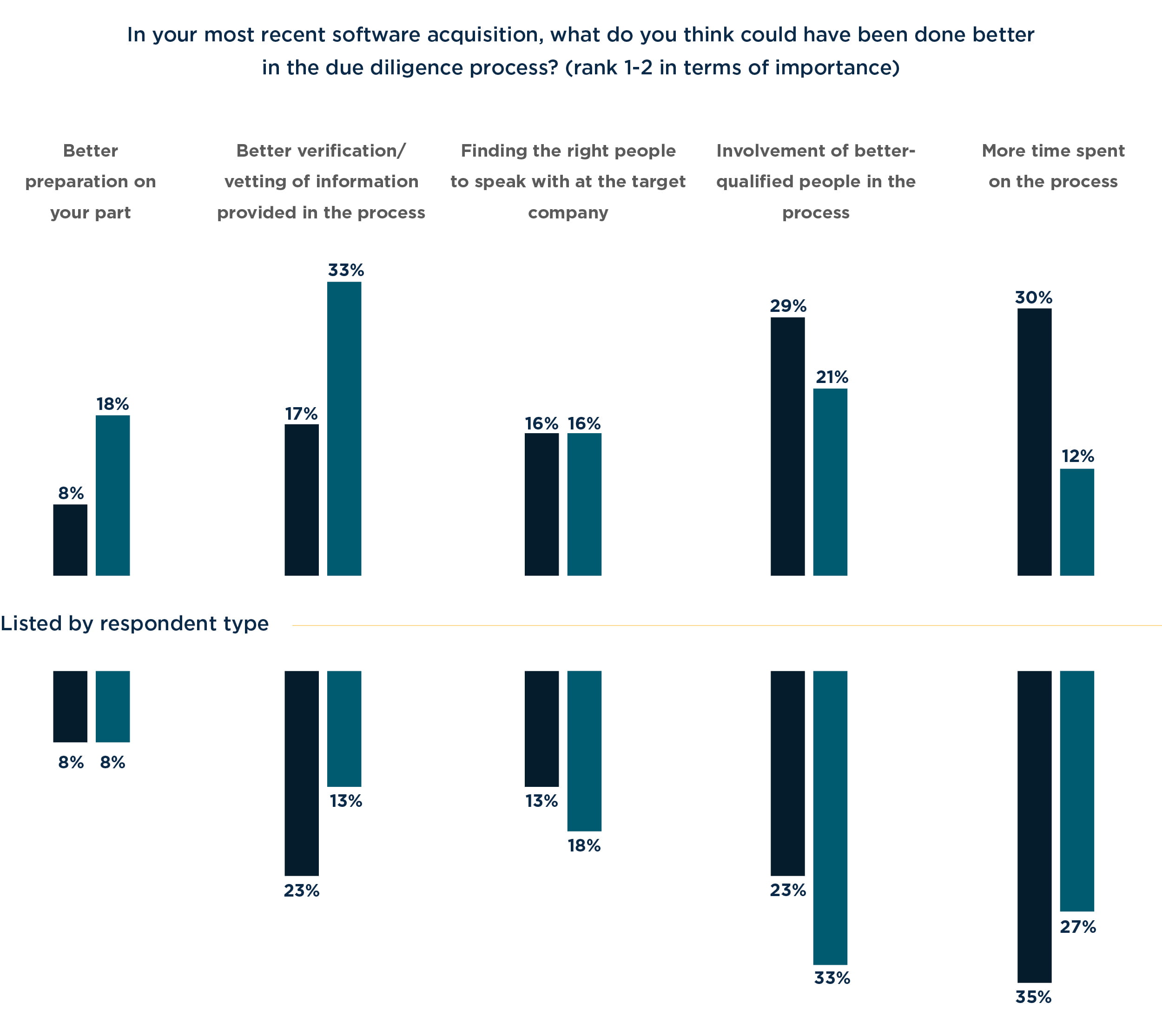

Lack of time is a common theme among the survey’s respondents. In fact, 30% contend that spending longer on the due diligence process is the single biggest way their most recent acquisition process could have been improved.

Many (29%) also say that the best way to improve their most recent due diligence experience would have been by involving more well-qualified specialists.

“We should have hired advisors and increased the audit team’s size,” says a managing director of one PE firm. “The management focused on the vendor due diligence report and less on the due diligence. This was a big mistake that proved to be a costly one. We also should have doubled-checked all the information that was provided to us during the due diligence.”

A third (33%) of respondents say the improved verification or vetting of information was the No. 2 item on their wish list for improving due diligence.

“It was critically important for us to gauge the target’s technology and we thought it would be better to involve external professionals who are better qualified,” says a partner at one PE firm. “This would help us identify the issues and at the same time prepare remediation steps that will help resolve the issues in a more timely and effective manner, which we are likely to follow in all of our next acquisition processes.”

Integration, preparation, and lessons

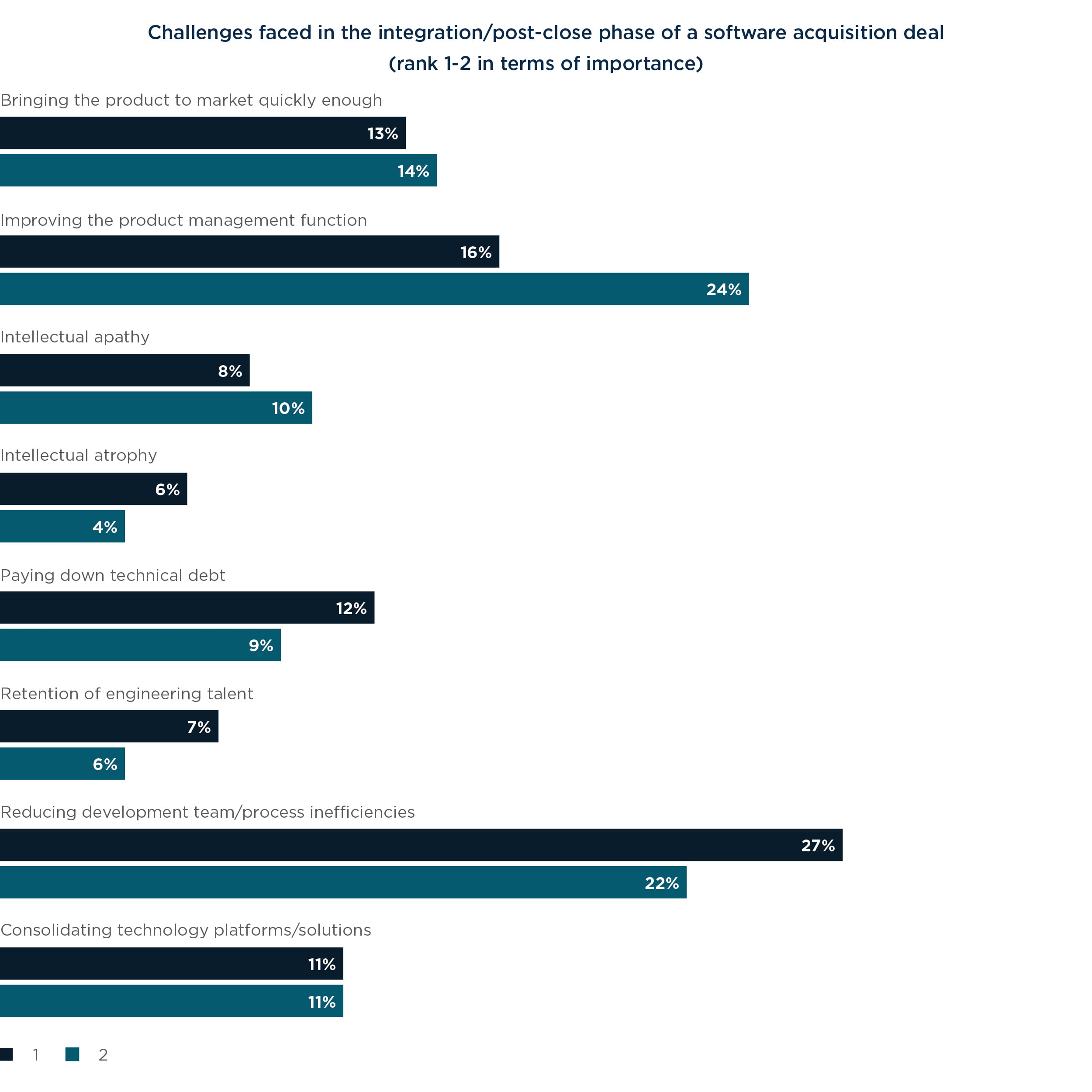

AFTER THE DEAL is completed, more than a quarter of respondents (27%) say the biggest challenge facing buyers is reducing inefficiencies in the development process and team.

Others say that their most pressing post-close problems are improving product management (16%) and making sure the target company’s products can be brought to market quickly (13%).

PE players and corporations diverge most in assessing the importance of bolstering the product management function, with 22% of PE firms claiming that issue as their top challenge compared with only 8% of corporations. A significant minority (12%) say their biggest post-close issue is paying down the technical debt of the acquisition. Others say intellectual apathy (8%) or intellectual atrophy (6%) are their main concerns post-close.

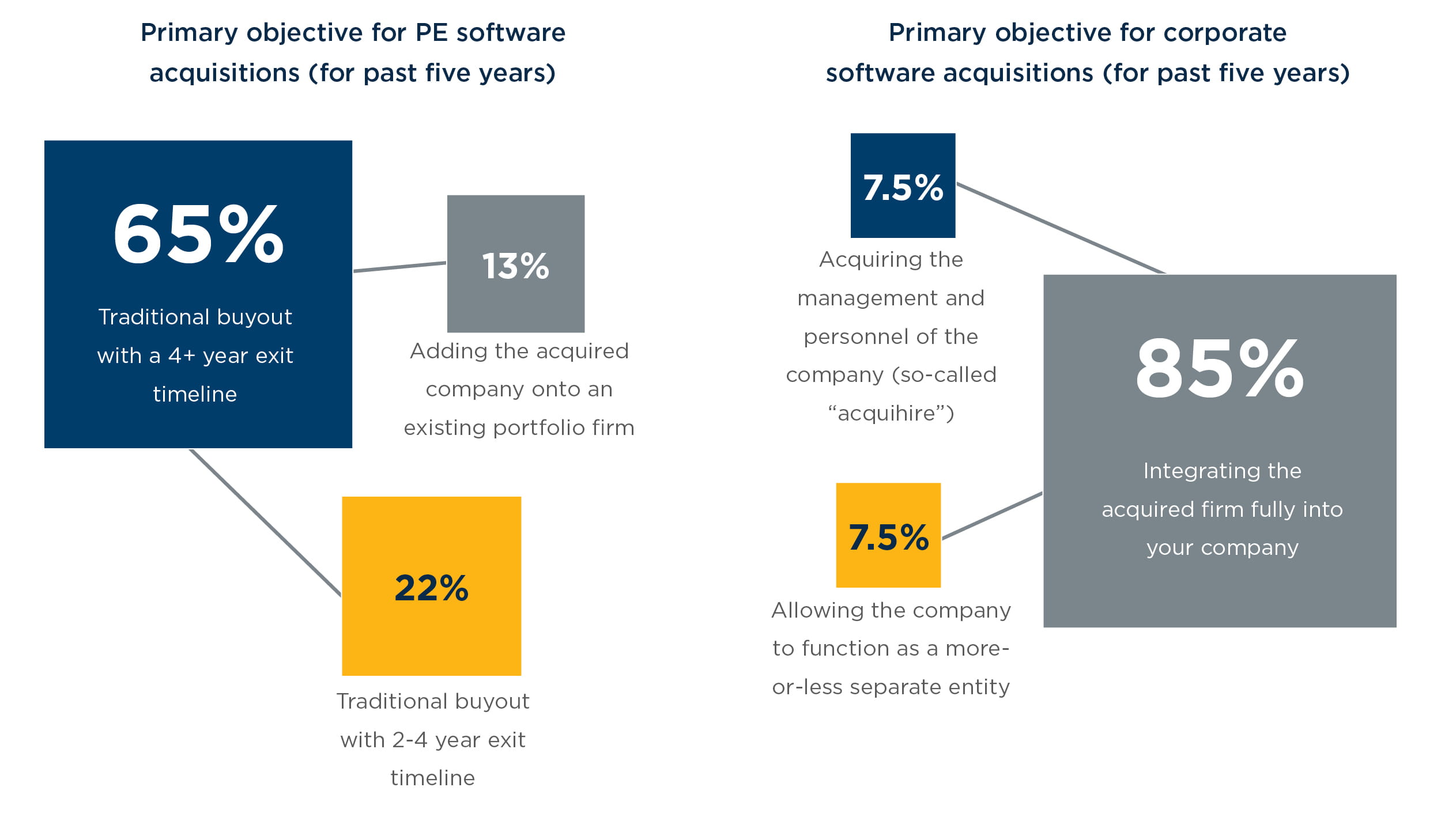

“Intellectual apathy is a major problem that’s difficult to deal with,” says a partner at an American PE firm. “Getting employees to understand the need for change and to innovate is not easy.” Most PE firms plan to hold on to their acquisitions in software for several years, with 65% saying that their primary objective has been to hold on to the firm for at least four years.

Fewer (22%) say they focus on tighter turnarounds, with two- to four-year exit strategies. Slightly more than 1 in 10 (13%) say their purchases in the software world have been primarily about bolting the acquired company onto another portfolio firm.

“The main reason we invest in software companies is to get long-term returns,” says one PE partner. “We invest for a few years. But we have also made acquisitions to get access to strong management that would add value to our portfolio, to help us get higher returns by creating value for the company.”

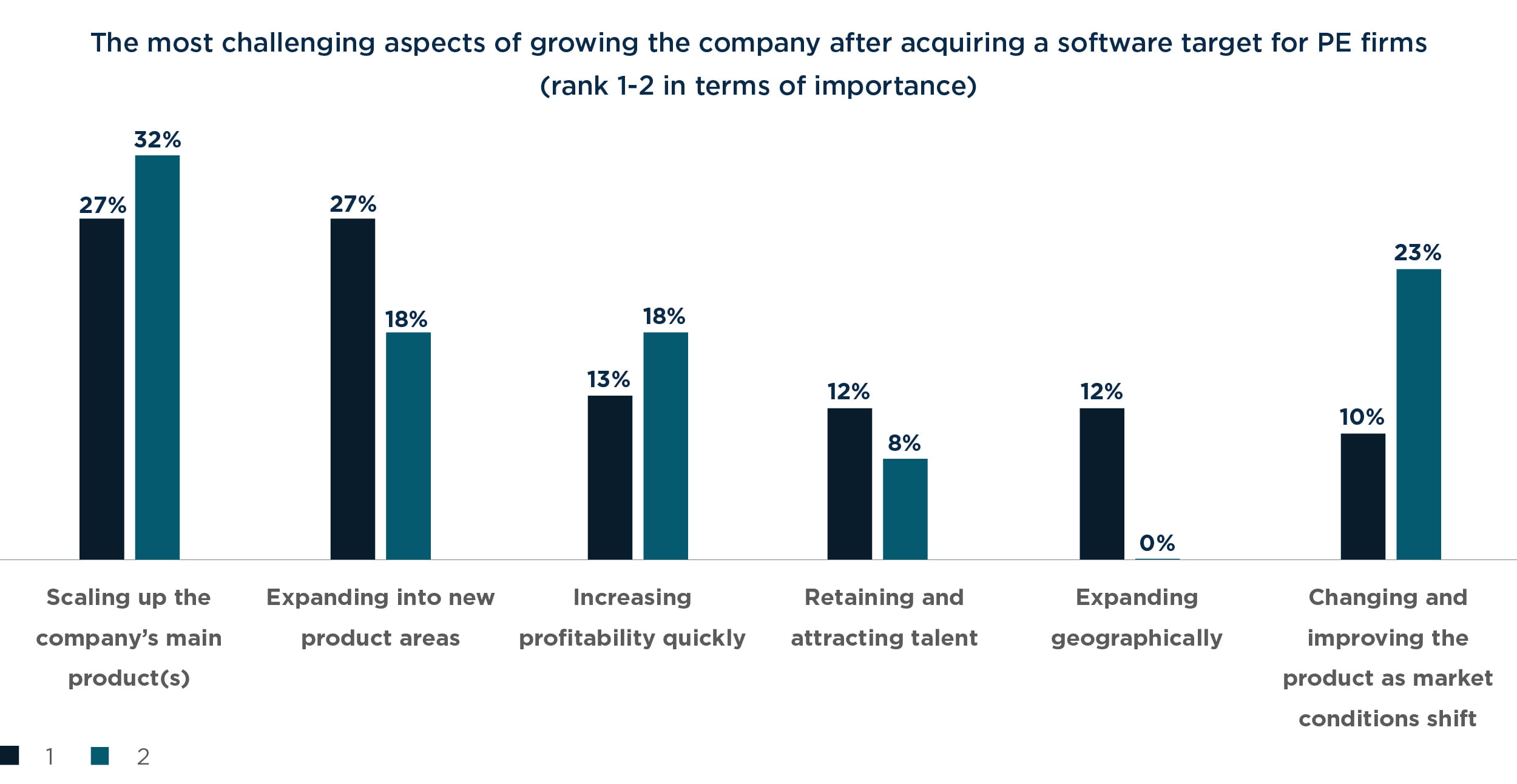

More than a quarter (27%) of PE respondents say the most challenging part of spurring growth in a new acquisition is the process of scaling up the purchased company’s main product, and 32% call it their second-biggest challenge.

On the other hand, taking the acquired firm in new directions also presents difficulties. Another 27% of respondents say expanding the firm into new product areas is the top challenge, and 18% call it their second-biggest problem.

“The most challenging aspect has been trying to further develop the existing goods and services of the company,” says a managing partner of a British PE firm. “This has been a difficult task and has not been simple to execute.”

Yet he also underscores the importance of having a strategy to bolster talent at the acquired firm. “Retaining and attracting new talent has also been a major challenge,” he says. “When undertaking the deal, we tried our best to keep the existing team because we felt they were very good, and we have been looking for new people and talent to further help us build our team and achieve our goals.”

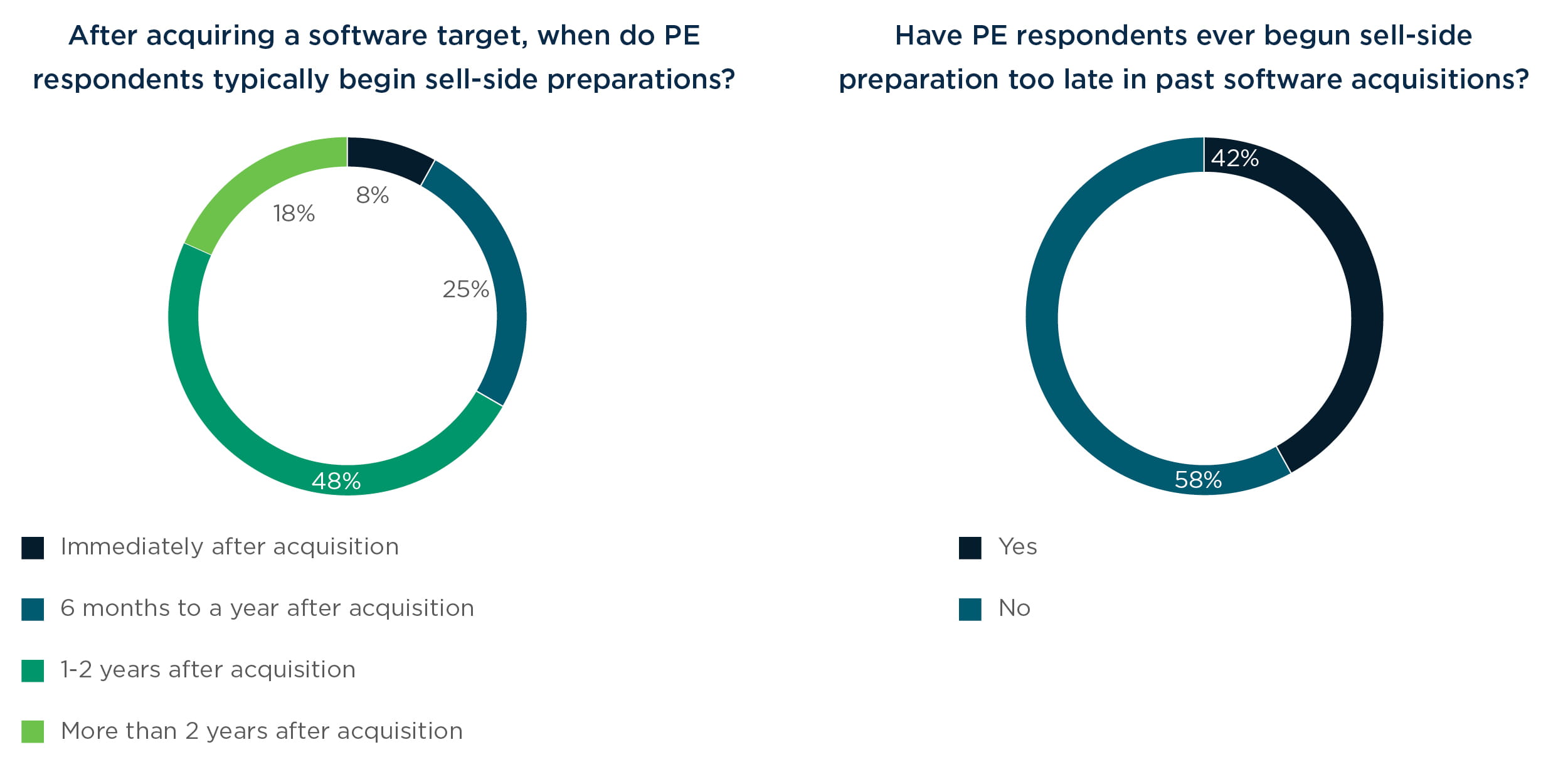

Almost half (48%) of PE respondents say that their top challenge when preparing a software company for sale is timing it right.

The No. 2 challenge is “telling potential buyers a great story about the company,” cited by 30% of PE firms. Meanwhile, 1 in 5 respondents (20%) say their top challenge is maintaining stability in the company that’s being put up for sale.

“Selling the company to the right buyer at the right time is ideal,” says the managing partner of an American PE firm. “It helps get the price they’re looking for and creates value for the company. And while the sale process is underway, the company needs to make sure there are no disruptions or problems that could affect growth or the overall sale.”

An overwhelming majority of corporate respondents (85%) say that their primary goal in software M&A is to integrate the acquired firm fully into their company. Yet that’s not the only reason they make acquisitions.

Alternatively, when asked to select all objectives that apply, a large minority (38%) say they have at some point in the past five years, been primarily motivated by acquiring the management or personnel of the target company in a so-called “acquihire.”

“There have been deals where we have acquired the company and retained its brand name, but we prefer integrating the company with ours,” says the chief strategy officer of a German corporation. “That makes it simpler to oversee operations and growth, and to make strategies that develop the business along the vision and goals we have in place for our company.”

When asked about the most important lessons they’ve learned from experience, respondents gave a multitude of responses. Some mention the need to dig deeply into the software of the target company.

“We have learned to take time and understand the software and platforms we are going to invest in,” says a senior director for corporate development at an American corporation. “Without understanding the platform, the integration process can be very problematic and lengthy. It can also disrupt services in both companies, which can mean losing customers.”

Others mention the need to pay special attention to differences in corporate culture when integrating an acquisition, and work closely with the target company’s management team to retain talent and ensure a smooth transition.

“Analyzing the management and corporate culture of the company we plan to work with is necessary and important,” says a partner in an American PE firm. “We’ve faced problems when we haven’t analyzed the team well. This may not be a major issue, but it can lead to slowdowns and impact business decisions.”

The need to ensure that a target company is in compliance with all relevant laws and regulations is echoed here also, as dealmakers reflect on the biggest challenges they face during a deal and the things they would have done differently.

“Paying closer attention to valuations and regulatory concerns while doing a cross-border acquisition is important,” says the CFO of a Canadian corporation. “The deal is more effective when these important processes are prioritized and the required approvals and licenses are completed well before the business starts to initiate their growth strategies.”

Several say the most important lesson they’ve learned is to invest enough time and effort into the due diligence process — to avoid surprises post-close, including, and importantly, in cybersecurity.

Conclusion

In June 2016, Marc Benioff, the CEO of Salesforce — which added another software acquisition to its portfolio in January 2017 after a buying spree of 10 companies in 2016 — told CNBC his industry was amid the most intense and exciting dealmaking season he’d ever seen.

“We’ve never seen more deals and more things happening,” Benioff said. Indeed, recent months have witnessed a rising frenzy of activity in software M&A, and this survey suggests the trend will continue.

One respondent, a managing director at a PE firm in Canada, sums up current dealmaker sentiment: “The economic conditions are improving and business demands for technology are growing, which is creating significant investment opportunities in the technology space, especially in software application development as it is being widely used throughout the various industries. The significant capital required by businesses to grow is attracting us to invest in more businesses than before.”

With vast amounts of cash on their books, both corporations and PE firms are prioritizing the search for quality over economy. Competition has pushed up valuations and tightened deal timeframes, all while heightening demand for companies run by talented management teams with products that can be scaled up and brought to market quickly.

West Monroe’s Sondag summarizes: “There’s so much capital to deploy, firms are looking for every way they can to win the race.”

Methodology

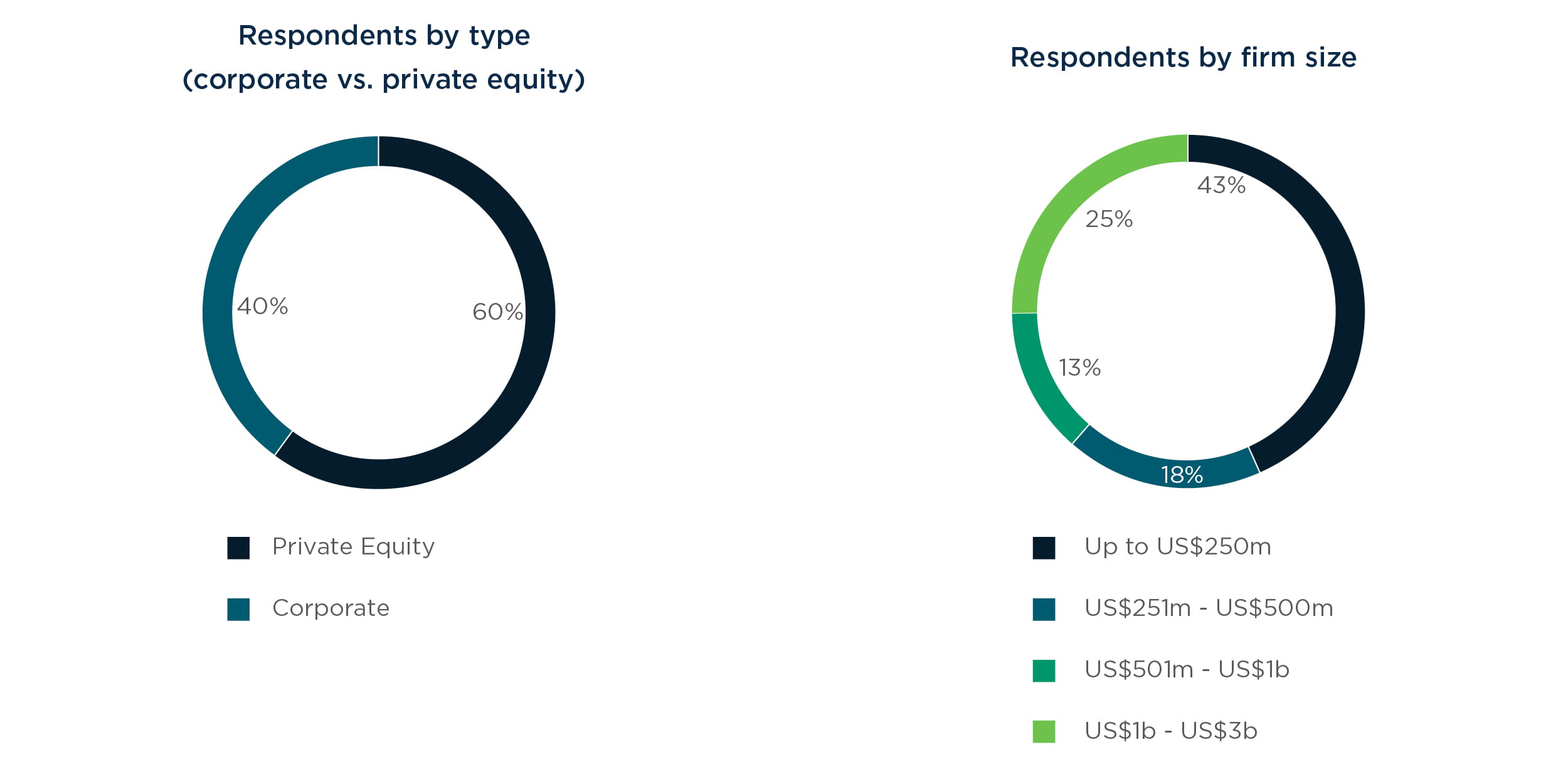

In Q1 2017, Mergermarket surveyed 100 senior global executives via phone to better understand the appetite, strategy, and processes for software M&A transactions. Respondents were split geographically across North America (80%) and EMEA (20%), and divided among corporate executives (40%) and private equity executives (60%). All respondents’ firms had acquired at least one software firm over the past three years.

Respondent profile

All respondent firms had completed at least one software acquisition in the past three years, and corporate respondents were split 43% with up to US$250 million in annual revenue; 18% with annual revenue between US$251 million and US$500 million; 13% between US$501 million and US$1 billion; and 25% between US$1 billion and US$3 billion.